Genocide

| Part of a series on |

| Genocide |

|---|

Issues |

|

Genocide of indigenous peoples |

European colonization of the Americas

|

Soviet genocide |

Ethnic cleansing in the Soviet Union

|

Nazi Holocaust and genocide (1941–1945) |

|

Cold War |

|

Contemporary genocide |

|

Related topics |

|

Category |

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

General forms

|

Specific forms |

Social

|

Manifestations

|

Policies

|

Countermeasures

|

Related topics

|

Genocide is intentional action to destroy a people (usually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group) in whole or in part. The hybrid word "genocide" is a combination of the Greek word génos ("race, people") and the Latin suffix -cide ("act of killing").[1] The United Nations Genocide Convention, which was established in 1948, defines genocide as "acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group".[2][3]

The term genocide was coined by Raphael Lemkin in his 1944 book Axis Rule in Occupied Europe;[4][5] it has been applied to the Holocaust, and many other mass killings including the genocide of indigenous peoples in the Americas, the Armenian Genocide, the Greek genocide, the Assyrian genocide, the Serbian genocide, the Holodomor, the Indonesian genocide,[6] the Guatemalan genocide, the 1971 Bangladesh genocide, the Cambodian genocide, and after 1980 the Bosnian genocide, the Kurdish genocide, the Darfur genocide, and the Rwandan genocide.[a]

The Political Instability Task Force estimated that, between 1956 and 2016, a total of forty-three genocides took place, causing the death of about 50 million people. The UNHCR estimated that a further 50 million had been displaced by such episodes of violence up to 2008.[7]

Contents

1 Origin of the term

2 As a crime

2.1 International law

2.2 Specific provisions

2.2.1 "Intent to destroy"

2.2.2 "In part"

2.3 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (CPPCG) coming into force

2.4 UN Security Council on genocide

2.5 Municipal law

3 Criticisms of the CPPCG and other definitions of genocide

4 International prosecution of genocide

4.1 By ad hoc tribunals

4.1.1 Nuremberg Tribunal (1945–1946)

4.1.2 International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (1993–2017)

4.1.3 International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (1994 to present)

4.1.4 Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (2003 to present)

4.2 By the International Criminal Court

4.2.1 Darfur, Sudan

5 Genocide in history

6 Stages of genocide, influences leading to genocide, and efforts to prevent it

7 See also

7.1 Research

8 Notes

9 References

10 Further reading

11 External links

Origin of the term

Before 1944, various terms, including "massacre", "crimes against humanity", and "extermination"[8] were used to describe intentional, systematic killings. In 1941, Winston Churchill, when describing the German invasion of the Soviet Union, spoke of "a crime without a name".[9]

In 1944, Raphael Lemkin created the term genocide in his book Axis Rule in Occupied Europe. The book describes the implementation of Nazi policies in occupied Europe, and cites earlier mass killings.[10] The term described the systematic destruction of a nation or people,[11] and the word was quickly adopted by many in the international community. The word genocide is the combination of the Greek prefix geno- (γένος, meaning 'race' or 'people') and caedere (the Latin word for "to kill").[12] The word genocide was used in indictments at the Nuremberg trials, held from 1945, but solely as a descriptive term, not yet as a formal legal term.[13]

According to Lemkin, genocide was "a coordinated strategy to destroy a group of people, a process that could be accomplished through total annihilation as well as strategies that eliminate key elements of the group's basic existence, including language, culture, and economic infrastructure".

Lemkin defined genocide as follows:

Generally speaking, genocide does not necessarily mean the immediate destruction of a nation, except when accomplished by mass killings of all members of a nation. It is intended rather to signify a coordinated plan of different actions aiming at the destruction of essential foundations of the life of national groups, with the aim of annihilating the groups themselves. The objectives of such a plan would be the disintegration of the political and social institutions, of culture, language, national feelings, religion, and the economic existence of national groups, and the destruction of the personal security, liberty, health, dignity, and even the lives of the individuals belonging to such groups.[12]

The preamble to the 1948 Genocide Convention (CPPCG) notes that instances of genocide have taken place throughout history.[14] But it was not until Lemkin coined the term and the prosecution of perpetrators of the Holocaust at the Nuremberg trials that the United Nations defined the crime of genocide under international law in the Genocide Convention.[15]

Lemkin's lifelong interest in the mass murder of populations in the 20th century was initially in response to the killing of Armenians in 1915[16][4][17] and later to the mass murders in Nazi-controlled Europe.[5] He referred to the Albigensian Crusade as "one of the most conclusive cases of genocide in religious history".[18] He dedicated his life to mobilizing the international community, to work together to prevent the occurrence of such events.[19] In a 1949 interview, Lemkin said "I became interested in genocide because it happened so many times. It happened to the Armenians, then after the Armenians, Hitler took action."[20]

As a crime

International law

Members of the Sonderkommando burn corpses of Jews in pits at Auschwitz II-Birkenau, an extermination camp

After the Holocaust, which had been perpetrated by Nazi Germany and its allies prior to and during World War II, Lemkin successfully campaigned for the universal acceptance of international laws defining and forbidding genocides. In 1946, the first session of the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution that "affirmed" that genocide was a crime under international law and enumerated examples of such events (but did not provide a full legal definition of the crime). In 1948, the UN General Assembly adopted the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (CPPCG) which defined the crime of genocide for the first time.[21]

.mw-parser-output .templatequoteoverflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequoteciteline-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0

Genocide is a denial of the right of existence of entire human groups, as homicide is the denial of the right to live of individual human beings; such denial of the right of existence shocks the conscience of mankind, results in great losses to humanity in the form of cultural and other contributions represented by these human groups, and is contrary to moral law and the spirit and aims of the United Nations. Many instances of such crimes of genocide have occurred when racial, religious, political and other groups have been destroyed, entirely or in part.

— UN Resolution 96(1), 11 December 1946

The CPPCG was adopted by the UN General Assembly on 9 December 1948[2] and came into effect on 12 January 1951 (Resolution 260 (III)). It contains an internationally recognized definition of genocide which has been incorporated into the national criminal legislation of many countries, and was also adopted by the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, which established the International Criminal Court (ICC). Article II of the Convention defines genocide as:

... any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

- (a) Killing members of the group;

- (b) Causing serious bodily harm, or harm to mental health, to members of the group;

- (c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

- (d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

- (e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

The first draft of the Convention included political killings, but these provisions were removed in a political and diplomatic compromise following objections from some countries, including the USSR, a permanent security council member.[22][23] The USSR argued that the Convention's definition should follow the etymology of the term,[23] and may have feared greater international scrutiny of its own mass killings.[22][24] Other nations feared that including political groups in the definition would invite international intervention in domestic politics.[23] However leading genocide scholar William Schabas states: "Rigorous examination of the travaux fails to confirm a popular impression in the literature that the opposition to inclusion of political genocide was some Soviet machination. The Soviet views were also shared by a number of other States for whom it is difficult to establish any geographic or social common denominator: Lebanon, Sweden, Brazil, Peru, Venezuela, the Philippines, the Dominican Republic, Iran, Egypt, Belgium, and Uruguay. The exclusion of political groups was in fact originally promoted by a non-governmental organization, the World Jewish Congress, and it corresponded to Raphael Lemkin's vision of the nature of the crime of genocide."[25]

The convention's purpose and scope was later described by the United Nations Security Council as follows:

The Convention was manifestly adopted for humanitarian and civilizing purposes. Its objectives are to safeguard the very existence of certain human groups and to affirm and emphasize the most elementary principles of humanity and morality. In view of the rights involved, the legal obligations to refrain from genocide are recognized as erga omnes.

When the Convention was drafted, it was already envisaged that it would apply not only to then existing forms of genocide, but also "to any method that might be evolved in the future with a view to destroying the physical existence of a group".[26] As emphasized in the preamble to the Convention, genocide has marred all periods of history, and it is this very tragic recognition that gives the concept its historical evolutionary nature.

The Convention must be interpreted in good faith, in accordance with the ordinary meaning of its terms, in their context, and in the light of its object and purpose. Moreover, the text of the Convention should be interpreted in such a way that a reason and a meaning can be attributed to every word. No word or provision may be disregarded or treated as superfluous, unless this is absolutely necessary to give effect to the terms read as a whole.[27]

Genocide is a crime under international law regardless of "whether committed in time of peace or in time of war" (art. I). Thus, irrespective of the context in which it occurs (for example, peace time, internal strife, international armed conflict or whatever the general overall situation) genocide is a punishable international crime.

— UN Commission of Experts that examined violations of international humanitarian law committed in the territory of the former Yugoslavia.[28]

Specific provisions

"Intent to destroy"

In 2007, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) noted in its judgement on Jorgic v. Germany case that, in 1992, the majority of legal scholars took the narrow view that "intent to destroy" in the CPPCG meant the intended physical-biological destruction of the protected group, and that this was still the majority opinion. But the ECHR also noted that a minority took a broader view, and did not consider biological-physical destruction to be necessary, as the intent to destroy a national, racial, religious or ethnic group was enough to qualify as genocide.[29]

In the same judgement, the ECHR reviewed the judgements of several international and municipal courts. It noted that the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia and the International Court of Justice had agreed with the narrow interpretation (that biological-physical destruction was necessary for an act to qualify as genocide). The ECHR also noted that at the time of its judgement, apart from courts in Germany (which had taken a broad view), that there had been few cases of genocide under other Convention states' municipal laws, and that "There are no reported cases in which the courts of these States have defined the type of group destruction the perpetrator must have intended in order to be found guilty of genocide."[30]

In the case of "Onesphore Rwabukombe", the German Supreme Court adhered to its previous judgement, and did not follow the narrow interpretation of the ICTY and the ICJ.[31]

"In part"

Armenian Genocide victims

The phrase "in whole or in part" has been subject to much discussion by scholars of international humanitarian law.[32] The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia found in Prosecutor v. Radislav Krstic – Trial Chamber I – Judgment – IT-98-33 (2001) ICTY8 (2 August 2001)[33] that Genocide had been committed. In Prosecutor v. Radislav Krstic – Appeals Chamber – Judgment – IT-98-33 (2004) ICTY 7 (19 April 2004)[34] paragraphs 8, 9, 10, and 11 addressed the issue of in part and found that "the part must be a substantial part of that group. The aim of the Genocide Convention is to prevent the intentional destruction of entire human groups, and the part targeted must be significant enough to have an impact on the group as a whole." The Appeals Chamber goes into details of other cases and the opinions of respected commentators on the Genocide Convention to explain how they came to this conclusion.

The judges continue in paragraph 12, "The determination of when the targeted part is substantial enough to meet this requirement may involve a number of considerations. The numeric size of the targeted part of the group is the necessary and important starting point, though not in all cases the ending point of the inquiry. The number of individuals targeted should be evaluated not only in absolute terms, but also in relation to the overall size of the entire group. In addition to the numeric size of the targeted portion, its prominence within the group can be a useful consideration. If a specific part of the group is emblematic of the overall group, or is essential to its survival, that may support a finding that the part qualifies as substantial within the meaning of Article 4 [of the Tribunal's Statute]."[35][36]

In paragraph 13 the judges raise the issue of the perpetrators' access to the victims: "The historical examples of genocide also suggest that the area of the perpetrators’ activity and control, as well as the possible extent of their reach, should be considered. ... The intent to destroy formed by a perpetrator of genocide will always be limited by the opportunity presented to him. While this factor alone will not indicate whether the targeted group is substantial, it can—in combination with other factors—inform the analysis."[34]

Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (CPPCG) coming into force

The Convention came into force as international law on 12 January 1951 after the minimum 20 countries became parties. At that time however, only two of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council were parties to the treaty: France and the Republic of China. The Soviet Union ratified in 1954, the United Kingdom in 1970, the People's Republic of China in 1983 (having replaced the Taiwan-based Republic of China on the UNSC in 1971), and the United States in 1988. This long delay in support for the Convention by the world's most powerful nations caused the Convention to languish for over four decades. Only in the 1990s did the international law on the crime of genocide begin to be enforced.[citation needed]

UN Security Council on genocide

UN Security Council Resolution 1674, adopted by the United Nations Security Council on 28 April 2006, "reaffirms the provisions of paragraphs 138 and 139 of the 2005 World Summit Outcome Document regarding the responsibility to protect populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity".[37] The resolution committed the Council to action to protect civilians in armed conflict.[38]

In 2008 the UN Security Council adopted resolution 1820, which noted that "rape and other forms of sexual violence can constitute war crimes, crimes against humanity or a constitutive act with respect to genocide".[39]

Municipal law

Since the Convention came into effect in January 1951 about 80 United Nations member states have passed legislation that incorporates the provisions of CPPCG into their municipal law.[40]

Criticisms of the CPPCG and other definitions of genocide

William Schabas has suggested that a permanent body as recommended by the Whitaker Report to monitor the implementation of the Genocide Convention, and require States to issue reports on their compliance with the convention (such as were incorporated into the United Nations Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture), would make the convention more effective.[41]

Writing in 1998 Kurt Jonassohn and Karin Björnson stated that the CPPCG was a legal instrument resulting from a diplomatic compromise. As such the wording of the treaty is not intended to be a definition suitable as a research tool, and although it is used for this purpose, as it has an international legal credibility that others lack, other definitions have also been postulated. Jonassohn and Björnson go on to say that none of these alternative definitions have gained widespread support for various reasons.[42]

Jonassohn and Björnson postulate that the major reason why no single generally accepted genocide definition has emerged is because academics have adjusted their focus to emphasise different periods and have found it expedient to use slightly different definitions to help them interpret events. For example, Frank Chalk and Kurt Jonassohn studied the whole of human history, while Leo Kuper and R. J. Rummel in their more recent works concentrated on the 20th century, and Helen Fein, Barbara Harff and Ted Gurr have looked at post World War II events. Jonassohn and Björnson are critical of some of these studies, arguing that they are too expansive, and conclude that the academic discipline of genocide studies is too young to have a canon of work on which to build an academic paradigm.[42]

The exclusion of social and political groups as targets of genocide in the CPPCG legal definition has been criticized by some historians and sociologists, for example M. Hassan Kakar in his book The Soviet Invasion and the Afghan Response, 1979–1982[43] argues that the international definition of genocide is too restricted,[44] and that it should include political groups or any group so defined by the perpetrator and quotes Chalk and Jonassohn: "Genocide is a form of one-sided mass killing in which a state or other authority intends to destroy a group, as that group and membership in it are defined by the perpetrator."[45] In turn some states such as Ethiopia,[46]France,[47] and Spain[48][49] include political groups as legitimate genocide victims in their anti-genocide laws.

Barbara Harff and Ted Gurr defined genocide as "the promotion and execution of policies by a state or its agents which result in the deaths of a substantial portion of a group ... [when] the victimized groups are defined primarily in terms of their communal characteristics, i.e., ethnicity, religion or nationality".[50] Harff and Gurr also differentiate between genocides and politicides by the characteristics by which members of a group are identified by the state. In genocides, the victimized groups are defined primarily in terms of their communal characteristics, i.e., ethnicity, religion or nationality. In politicides the victim groups are defined primarily in terms of their hierarchical position or political opposition to the regime and dominant groups.[51][52] Daniel D. Polsby and Don B. Kates, Jr. state that "we follow Harff's distinction between genocides and 'pogroms', which she describes as 'short-lived outbursts by mobs, which, although often condoned by authorities, rarely persist'. If the violence persists for long enough, however, Harff argues, the distinction between condonation and complicity collapses."[53][54]

According to R. J. Rummel, genocide has 3 different meanings. The ordinary meaning is murder by government of people due to their national, ethnic, racial, or religious group membership. The legal meaning of genocide refers to the international treaty, the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (CPPCG). This also includes non-killings that in the end eliminate the group, such as preventing births or forcibly transferring children out of the group to another group. A generalized meaning of genocide is similar to the ordinary meaning but also includes government killings of political opponents or otherwise intentional murder. It is to avoid confusion regarding what meaning is intended that Rummel created the term democide for the third meaning.[55]

Highlighting the potential for state and non-state actors to commit genocide in the 21st century, for example, in failed states or as non-state actors acquire weapons of mass destruction, Adrian Gallagher defined genocide as 'When a source of collective power (usually a state) intentionally uses its power base to implement a process of destruction in order to destroy a group (as defined by the perpetrator), in whole or in substantial part, dependent upon relative group size'.[56] The definition upholds the centrality of intent, the multidimensional understanding of destroy, broadens the definition of group identity beyond that of the 1948 definition yet argues that a substantial part of a group has to be destroyed before it can be classified as genocide.

International prosecution of genocide

By ad hoc tribunals

Nuon Chea, the Khmer Rouge's chief ideologist, before the Cambodian Genocide Tribunal on 5 December 2011.

All signatories to the CPPCG are required to prevent and punish acts of genocide, both in peace and wartime, though some barriers make this enforcement difficult. In particular, some of the signatories—namely, Bahrain, Bangladesh, India, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, the United States, Vietnam, Yemen, and former Yugoslavia—signed with the proviso that no claim of genocide could be brought against them at the International Court of Justice without their consent.[57] Despite official protests from other signatories (notably Cyprus and Norway) on the ethics and legal standing of these reservations, the immunity from prosecution they grant has been invoked from time to time, as when the United States refused to allow a charge of genocide brought against it by former Yugoslavia following the 1999 Kosovo War.[58]

It is commonly accepted that, at least since World War II, genocide has been illegal under customary international law as a peremptory norm, as well as under conventional international law. Acts of genocide are generally difficult to establish for prosecution, because a chain of accountability must be established. International criminal courts and tribunals function primarily because the states involved are incapable or unwilling to prosecute crimes of this magnitude themselves.[citation needed]

Nuremberg Tribunal (1945–1946)

The Nazi leaders at the Palace of Justice, Nuremberg

The Nazi leaders who were prosecuted shortly after World War II for taking part in the Holocaust, and other mass murders, were charged under existing international laws, such as crimes against humanity, as the crime of "genocide' was not formally defined until the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (CPPCG). Nevertheless, the recently coined term[59] appeared in the indictment of the Nazi leaders, Count 3, which stated that those charged had "conducted deliberate and systematic genocide—namely, the extermination of racial and national groups—against the civilian populations of certain occupied territories in order to destroy particular races and classes of people, and national, racial or religious groups, particularly Jews, Poles, Gypsies and others."[60]

International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (1993–2017)

The cemetery at the Srebrenica-Potočari Memorial and Cemetery to Genocide Victims

The term Bosnian genocide is used to refer either to the killings committed by Serb forces in Srebrenica in 1995,[61] or to ethnic cleansing that took place elsewhere during the 1992–1995 Bosnian War.[62]

In 2001, the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) judged that the 1995 Srebrenica massacre was an act of genocide.[63] On 26 February 2007, the International Court of Justice (ICJ), in the Bosnian Genocide Case upheld the ICTY's earlier finding that the massacre in Srebrenica and Zepa constituted genocide, but found that the Serbian government had not participated in a wider genocide on the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina during the war, as the Bosnian government had claimed.[64]

On 12 July 2007, European Court of Human Rights when dismissing the appeal by Nikola Jorgić against his conviction for genocide by a German court (Jorgic v. Germany) noted that the German courts wider interpretation of genocide has since been rejected by international courts considering similar cases.[65][66][67] The ECHR also noted that in the 21st century "Amongst scholars, the majority have taken the view that ethnic cleansing, in the way in which it was carried out by the Serb forces in Bosnia and Herzegovina in order to expel Muslims and Croats from their homes, did not constitute genocide. However, there are also a considerable number of scholars who have suggested that these acts did amount to genocide, and the ICTY has found in the Momcilo Krajisnik case that the actus reus of genocide was met in Prijedor "With regard to the charge of genocide, the Chamber found that in spite of evidence of acts perpetrated in the municipalities which constituted the actus reus of genocide".[68]

About 30 people have been indicted for participating in genocide or complicity in genocide during the early 1990s in Bosnia. To date, after several plea bargains and some convictions that were successfully challenged on appeal two men, Vujadin Popović and Ljubiša Beara, have been found guilty of committing genocide, Zdravko Tolimir has been found guilty of committing genocide and conspiracy to commit genocide, and two others, Radislav Krstić and Drago Nikolić, have been found guilty of aiding and abetting genocide. Three others have been found guilty of participating in genocides in Bosnia by German courts, one of whom Nikola Jorgić lost an appeal against his conviction in the European Court of Human Rights. A further eight men, former members of the Bosnian Serb security forces were found guilty of genocide by the State Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina (See List of Bosnian genocide prosecutions).

Slobodan Milošević, as the former President of Serbia and of Yugoslavia, was the most senior political figure to stand trial at the ICTY. He died on 11 March 2006 during his trial where he was accused of genocide or complicity in genocide in territories within Bosnia and Herzegovina, so no verdict was returned. In 1995, the ICTY issued a warrant for the arrest of Bosnian Serbs Radovan Karadžić and Ratko Mladić on several charges including genocide. On 21 July 2008, Karadžić was arrested in Belgrade, and later tried in The Hague accused of genocide among other crimes.[69] On 24 March 2016, Karadžić was found guilty of genocide in Srebrenica, war crimes and crimes against humanity, 10 of the 11 charges in total, and sentenced to 40 years' imprisonment.[70][71] Mladić was arrested on 26 May 2011 in Lazarevo, Serbia,[72] and was tried in The Hague. The verdict, delivered on 22 November 2017 found Mladić guilty of 10 of the 11 charges, including genocide and he was sentenced to life imprisonment.[73]

International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (1994 to present)

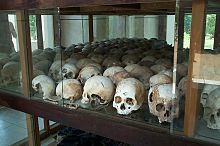

Victims of the 1994 Rwandan genocide

The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) is a court under the auspices of the United Nations for the prosecution of offenses committed in Rwanda during the genocide which occurred there during April 1994, commencing on 6 April. The ICTR was created on 8 November 1994 by the Security Council of the United Nations in order to judge those people responsible for the acts of genocide and other serious violations of the international law performed in the territory of Rwanda, or by Rwandan citizens in nearby states, between 1 January and 31 December 1994.

So far, the ICTR has finished nineteen trials and convicted twenty seven accused persons. On 14 December 2009 two more men were accused and convicted for their crimes. Another twenty five persons are still on trial. Twenty-one are awaiting trial in detention, two more added on 14 December 2009. Ten are still at large.[74] The first trial, of Jean-Paul Akayesu, began in 1997. In October 1998, Akayesu was sentenced to life imprisonment. Jean Kambanda, interim Prime Minister, pleaded guilty.

Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (2003 to present)

Rooms of the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum contain thousands of photos taken by the Khmer Rouge of their victims.

Skulls in the Choeung Ek.

The Khmer Rouge, led by Pol Pot, Ta Mok and other leaders, organized the mass killing of ideologically suspect groups. The total number of victims is estimated at approximately 1.7 million Cambodians between 1975–1979, including deaths from slave labour.[75]

On 6 June 2003 the Cambodian government and the United Nations reached an agreement to set up the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) which would focus exclusively on crimes committed by the most senior Khmer Rouge officials during the period of Khmer Rouge rule of 1975–1979.[76] The judges were sworn in early July 2006.[77][78][79]

The genocide charges related to killings of Cambodia's Vietnamese and Cham minorities, which is estimated to make up tens of thousand killings and possibly more[80][81]

The investigating judges were presented with the names of five possible suspects by the prosecution on 18 July 2007.[77][82]

Kang Kek Iew was formally charged with war crime and crimes against humanity and detained by the Tribunal on 31 July 2007. He was indicted on charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity on 12 August 2008.[83] His appeal against his conviction for war crimes and crimes against humanity was rejected on 3 February 2012, and he is serving a sentence of life imprisonment.[84]

Nuon Chea, a former prime minister, who was indicted on charges of genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and several other crimes under Cambodian law on 15 September 2010. He was transferred into the custody of the ECCC on 19 September 2007. His trial started on 27 June 2011[80][85] and ended on 7 August 2014, with a life sentence imposed for crimes against humanity.[86]

Khieu Samphan, a former head of state, who was indicted on charges of genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and several other crimes under Cambodian law on 15 September 2010. He was transferred into the custody of the ECCC on 19 September 2007. His trial began on 27 June 2011.[80][85] and also ended on 7 August 2014, with a life sentence imposed for crimes against humanity.[86]

Ieng Sary, a former foreign minister, who was indicted on charges of genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and several other crimes under Cambodian law on 15 September 2010. He was transferred into the custody of the ECCC on 12 November 2007. His trial started on 27 June 2011, and ended with his death on 14 March 2013. He was never convicted.[80][85]

Ieng Thirith, a former minister for social affairs and wife of Ieng Sary, who was indicted on charges of genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and several other crimes under Cambodian law on 15 September 2010. She was transferred into the custody of the ECCC on 12 November 2007. Proceedings against her have been suspended pending a health evaluation.[85][87]

There has been disagreement between some of the international jurists and the Cambodian government over whether any other people should be tried by the Tribunal.[82]

By the International Criminal Court

Since 2002, the International Criminal Court can exercise its jurisdiction if national courts are unwilling or unable to investigate or prosecute genocide, thus being a "court of last resort," leaving the primary responsibility to exercise jurisdiction over alleged criminals to individual states. Due to the United States concerns over the ICC, the United States prefers to continue to use specially convened international tribunals for such investigations and potential prosecutions.[88]

Darfur, Sudan

A mother with her sick baby at Abu Shouk IDP camp in North Darfur

There has been much debate over categorizing the situation in Darfur as genocide.[89] The ongoing conflict in Darfur, Sudan, which started in 2003, was declared a "genocide" by United States Secretary of State Colin Powell on 9 September 2004 in testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.[90] Since that time however, no other permanent member of the UN Security Council has done so. In fact, in January 2005, an International Commission of Inquiry on Darfur, authorized by UN Security Council Resolution 1564 of 2004, issued a report to the Secretary-General stating that "the Government of the Sudan has not pursued a policy of genocide."[91] Nevertheless, the Commission cautioned that "The conclusion that no genocidal policy has been pursued and implemented in Darfur by the Government authorities, directly or through the militias under their control, should not be taken in any way as detracting from the gravity of the crimes perpetrated in that region. International offences such as the crimes against humanity and war crimes that have been committed in Darfur may be no less serious and heinous than genocide."[91]

In March 2005, the Security Council formally referred the situation in Darfur to the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, taking into account the Commission report but without mentioning any specific crimes.[92] Two permanent members of the Security Council, the United States and China, abstained from the vote on the referral resolution.[93] As of his fourth report to the Security Council, the Prosecutor has found "reasonable grounds to believe that the individuals identified [in the UN Security Council Resolution 1593] have committed crimes against humanity and war crimes," but did not find sufficient evidence to prosecute for genocide.[94]

In April 2007, the Judges of the ICC issued arrest warrants against the former Minister of State for the Interior, Ahmad Harun, and a Militia

Janjaweed leader, Ali Kushayb, for crimes against humanity and war crimes.[95]

On 14 July 2008, prosecutors at the International Criminal Court (ICC), filed ten charges of war crimes against Sudan's President Omar al-Bashir: three counts of genocide, five of crimes against humanity and two of murder. The ICC's prosecutors claimed that al-Bashir "masterminded and implemented a plan to destroy in substantial part" three tribal groups in Darfur because of their ethnicity.

On 4 March 2009, the ICC issued a warrant of arrest for Omar Al Bashir, President of Sudan as the ICC Pre-Trial Chamber I concluded that his position as head of state does not grant him immunity against prosecution before the ICC. The warrant was for war crimes and crimes against humanity. It did not include the crime of genocide because the majority of the Chamber did not find that the prosecutors had provided enough evidence to include such a charge.[96] Later the decision was changed by the Appeals Panel and after issuing the second decision, charges against Omar al-Bashir include three counts of genocide.[97]

Genocide in history

Naked Soviet POWs held by the Nazis in Mauthausen concentration camp. "... the murder of at least 3.3 million Soviet POWs is one of the least-known of modern genocides; there is still no full-length book on the subject in English." —Adam Jones[98]

The concept of genocide can be applied to historical events of the past. The preamble to the CPPCG states that "at all periods of history genocide has inflicted great losses on humanity."

Revisionist attempts to challenge or affirm claims of genocide are illegal in some countries. For example, several European countries ban the denial of the Holocaust or the Armenian Genocide, while in Turkey referring to the mass killings of Armenians, Greeks, Assyrians and Maronites as genocides may be prosecuted under Article 301.[99]

William Rubinstein argues that the origin of 20th century genocides can be traced back to the collapse of the elite structure and normal modes of government in parts of Europe following the First World War:

The 'Age of Totalitarianism' included nearly all of the infamous examples of genocide in modern history, headed by the Jewish Holocaust, but also comprising the mass murders and purges of the Communist world, other mass killings carried out by Nazi Germany and its allies, and also the Armenian genocide of 1915. All these slaughters, it is argued here, had a common origin, the collapse of the elite structure and normal modes of government of much of central, eastern and southern Europe as a result of the First World War, without which surely neither Communism nor Fascism would have existed except in the minds of unknown agitators and crackpots.

— William Rubinstein, Genocide: a history[100]

Stages of genocide, influences leading to genocide, and efforts to prevent it

For genocide to happen, there must be certain preconditions. Foremost among them is a national culture that does not place a high value on human life. A totalitarian society, with its assumed superior ideology, is also a precondition for genocidal acts.[101] In addition, members of the dominant society must perceive their potential victims as less than fully human: as "pagans," "savages," "uncouth barbarians," "unbelievers," "effete degenerates," "ritual outlaws," "racial inferiors," "class antagonists," "counterrevolutionaries," and so on.[102] In themselves, these conditions are not enough for the perpetrators to commit genocide. To do that—that is, to commit genocide—the perpetrators need a strong, centralized authority and bureaucratic organization as well as pathological individuals and criminals. Also required is a campaign of vilification and dehumanization of the victims by the perpetrators, who are usually new states or new regimes attempting to impose conformity to a new ideology and its model of society.[101]

— M. Hassan Kakar[103]

In 1996 Gregory Stanton, the president of Genocide Watch, presented a briefing paper called "The 8 Stages of Genocide" at the United States Department of State.[104] In it he suggested that genocide develops in eight stages that are "predictable but not inexorable".[104][105]

The Stanton paper was presented to the State Department, shortly after the Rwandan Genocide and much of its analysis is based on why that genocide occurred. The preventative measures suggested, given the briefing paper's original target audience, were those that the United States could implement directly or indirectly by using its influence on other governments.

| Stage | Characteristics | Preventive measures |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Classification | People are divided into "us and them". | "The main preventive measure at this early stage is to develop universalistic institutions that transcend... divisions." |

| 2. Symbolization | "When combined with hatred, symbols may be forced upon unwilling members of pariah groups..." | "To combat symbolization, hate symbols can be legally forbidden as can hate speech". |

| 3. Dehumanization | "One group denies the humanity of the other group. Members of it are equated with animals, vermin, insects, or diseases." | "Local and international leaders should condemn the use of hate speech and make it culturally unacceptable. Leaders who incite genocide should be banned from international travel and have their foreign finances frozen." |

| 4. Organization | "Genocide is always organized... Special army units or militias are often trained and armed..." | "The U.N. should impose arms embargoes on governments and citizens of countries involved in genocidal massacres, and create commissions to investigate violations" |

| 5. Polarization | "Hate groups broadcast polarizing propaganda..." | "Prevention may mean security protection for moderate leaders or assistance to human rights groups...Coups d’état by extremists should be opposed by international sanctions." |

| 6. Preparation | "Victims are identified and separated out because of their ethnic or religious identity..." | "At this stage, a Genocide Emergency must be declared. ..." |

| 7. Extermination | "It is 'extermination' to the killers because they do not believe their victims to be fully human". | "At this stage, only rapid and overwhelming armed intervention can stop genocide. Real safe areas or refugee escape corridors should be established with heavily armed international protection." |

| 8. Denial | "The perpetrators... deny that they committed any crimes..." | "The response to denial is punishment by an international tribunal or national courts" |

In April 2012, it was reported that Stanton would soon be officially adding two new stages, Discrimination and Persecution, to his original theory, which would make for a 10-stage theory of genocide.[106]

In a paper for the Social Science Research Council Dirk Moses criticises the Stanton approach concluding:

In view of this rather poor record of ending genocide, the question needs to be asked why the "genocide studies" paradigm cannot predict and prevent genocides with any accuracy and reliability. The paradigm of "genocide studies," as currently constituted in North America in particular, has both strengths and limitations. While the moral fervor and public activism is admirable and salutary, the paradigm appears blind to its own implication in imperial projects that are themselves as much part of the problem as they are part of the solution. The US government called Darfur a genocide to appease domestic lobbies, and because the statement cost it nothing. Darfur will end when it suits the great powers that have a stake in the region.

— Dirk Moses[107]

Other authors have focused on the structural conditions leading up to genocide and the psychological and social processes that create an evolution toward genocide. Ervin Staub showed that economic deterioration and political confusion and disorganization were starting points of increasing discrimination and violence in many instances of genocides and mass killing. They lead to scapegoating a group and ideologies that identified that group as an enemy. A history of devaluation of the group that becomes the victim, past violence against the group that becomes the perpetrator leading to psychological wounds, authoritarian cultures and political systems, and the passivity of internal and external witnesses (bystanders) all contribute to the probability that the violence develops into genocide.[108] Intense conflict between groups that is unresolved, becomes intractable and violent can also lead to genocide. The conditions that lead to genocide provide guidance to early prevention, such as humanizing a devalued group, creating ideologies that embrace all groups, and activating bystander responses. There is substantial research to indicate how this can be done, but information is only slowly transformed into action.[109]

Kjell Anderson uses a dichotomistic classification of genocides: "hot genocides, motivated by hate and the victims’ threatening nature, with low-intensity cold genocides, rooted in victims’ supposed inferiority."[110]

See also

- Countervalue

- Crimes against humanity

- Cultural genocide

- Death squad

- Dehumanization

- Democide

- Effects of genocide on youth

- Ethnic cleansing

- Ethnic hatred

- Ethnocide

- Extrajudicial killing

- Forced displacement

- Forensic anthropology

- Gendercide

- Genocidal rape

- Genocide education

- Homicide

- Infanticide

- Institutional racism

- Involuntary euthanasia

- Local extinction

- Mass Atrocity crimes

- Mass murder

- Omnicide

- Policide

- Political cleansing of population

- Population growth#Human population growth rate

- Religious cleansing

- Ritualcide

- Social cleansing

- Utilitarian genocide

Research

- Center for the Study of Genocide, Conflict Resolution, and Human Rights

- International Association of Genocide Scholars

Notes

^ For more complete lists, see List of genocides by death toll or Genocides in history.

References

^ Stanton, Gregory H., What is genocide?, Genocide Watch.mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em.

^ ab "Legal definition of genocide" (PDF). United Nations. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

^ News, VOA. "What Is Genocide?". voanews.com. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

^ ab William Schabas. "Genocide in international law: the crimes of crimes". Cambridge University Press, 2000, p. 25: "Lemkin's interest in the subject dates to his days as a student at Lvov University, when he intently followed attempts to prosecute the perpetration of the massacres of the Armenians."

^ ab Power 2003, pp. 22–29.

^ Robinson, Geoffrey B. (2018). The Killing Season: A History of the Indonesian Massacres, 1965-66. Princeton University Press. p. 4. ISBN 9781400888863.And while there is still no consensus on the matter, some scholars have described the Indonesian violence as genocide.

^ Charles H. Anderton, Jurgen Brauer, ed. (2016). Economic Aspects of Genocides, Other Mass Atrocities, and Their Prevention. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199378296.

^ Trafzer, Clifford E.; Hyer, Joel R. (1999). Exterminate Them! Written Accounts of the Murder, Rape, and Slavery of Native Americans during the California Gold Rush, 1848-1868. Michigan State University Press.

^ Churchill, Winston (August 24, 1941). Prime Minister Winston Churchill's Broadcast to the World About the Meeting With President Roosevelt (Speech). British Library of Information – via ibiblio.

^ "Coining a Word and Championing a Cause: The Story of Raphael Lemkin". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM), Holocaust Encyclopedia.Lemkin's memoirs detail early exposure to the history of Ottoman attacks against Armenians (which most scholars believe constitute genocide), antisemitic pogroms, and other histories of group-targeted violence as key to forming his beliefs about the need for legal protection of groups.

^ Taylor, Telford (1982-03-28). "When people kill a people". The New York Times. Retrieved 2016-12-12. "In 1943, in the course of his monumental study Axis Rule in Occupied Europe, the late Raphael Lemkin coined the word genocide – from the Greek genos (race or tribe) and the Latin cide (killing) – to describe the deliberate 'destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group'."

^ ab Lemkin 2008, p. 79.

^ "What Is Genocide?", Holocaust Encyclopedia, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 24 June 2014.

^ Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. Retrieved 2008-10-22. Archived 2 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

^ "Coining a Word and Championing a Cause: The Story of Raphael Lemkin". www.ushmm.org. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

^ Yair Auron. The Banality of Denial: Israel and the Armenian Genocide. Transaction Publishers, 2004, p. 9: "... when Raphael Lemkin coined the word genocide in 1944 he cited the 1915 annihilation of Armenians as a seminal example of genocide."

^ A. Dirk Moses. Genocide and settler society: frontier violence and stolen indigenous children in Australian history. Berghahn Books, 2004, p. 21: "Indignant that the perpetrators of the Armenian genocide had largely escaped prosecution, Lemkin, who was a young state prosecutor in Poland, began lobbying in the early 1930s for international law to criminalize the destruction of such groups."

^ Raphael Lemkin (2012). Steven Leonard Jacobs, ed. Lemkin on Genocide. Lexington Books. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-7391-4526-5. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

^ Rothenberg, Daniel. "Genocide". Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity. Ed. Dinah L. Shelton. Vol. 1. Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA, 2005. 395–397. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 4 March 2015.

^ Stanley, Alessandra (Apr 17, 2006). "A PBS Documentary Makes Its Case for the Armenian Genocide, With or Without a Debate". New York Times. Retrieved Aug 7, 2012.

^ Rubinstein, W. D. (2004). Genocide: a history. Pearson Education. p. 308. ISBN 0-582-50601-8.

^ ab Robert Gellately & Ben Kiernan (2003). The Specter of Genocide: Mass Murder in Historical Perspective. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 267. ISBN 0-521-52750-3.

^ abc Staub, Ervin (31 July 1992). The Roots of Evil: The Origins of Genocide and Other Group Violence. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 8. ISBN 0-521-42214-0.

^ "USSR--Genocide and Mass Murder". www.hawaii.edu. Retrieved 2018-08-30.

^ William A. Schabas (2009), Genocide in International Law: The Crime of Crimes, 2nd Ed., pg 160

^ From a statement made by Mr. Morozov, representative of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, on 19 April 1948 during the debate in the Ad Hoc Committee on Genocide (E/AC.25/SR.12).

^ See Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, opened for signature on 23 May 1969, United Nations Treaty Series, vol. 1155, No. I-18232.

^ Mandate, structure and methods of work: Genocide I Archived 21 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine. of the UN Commission of Experts Archived 13 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine. to examine violations of international humanitarian law committed in the territory of the former Yugoslavia, created by Security Council resolution 780 (1992) of 6 October 1992.

^ European Court of Human Rights Judgement in Jorgic v. Germany (Application no. 74613/01) paragraphs 18, 36,74

^ European Court of Human Rights Judgement in Jorgic v. Germany (Application no. 74613/01) paragraphs 43–46

^ BGH, Urteil v. 21.05.2015 – 3 StR 575/14, analysed with respect to genocidal intent in La Revue des Droits de l'Homme by Natascha Kersting (La poursuite pénale du génocide rwandais devant les juridictions allemandes: L'intention de détruire dans l'affaire "Onesphore Rwabukombe"), https://revdh.revues.org/2539.

^ "What is Genocide?" Archived 5 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine. McGill Faculty of Law (McGill University)

^ Prosecutor v. Radislav Krstic – Trial Chamber I – Judgment – IT-98-33 (2001) ICTY8 (2 August 2001)

^ ab "The Prosecutor v. Limaj et al. - Decision on Prosecution's Motion to Amend the Amended Indictment - Trial Chamber - en IT-03-66 [2004] ICTY 7 (12 February 2004)". www.worldlii.org. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

^ Prosecutor v. Radislav Krstic – Appeals Chamber – Judgment – IT-98-33 (2004) ICTY 7 (19 April 2004) See Paragraph 6: "Article 4 of the Tribunal's Statute, like the Genocide Convention, covers certain acts done with "intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such".

^ Statute of the International Tribunal for the Prosecution of Persons Responsible for Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of the Former Yugoslavia since 1991, U.N. Doc. S/25704 at 36, annex (1993) and S/25704/Add.1 (1993), adopted by Security Council on 25 May 1993, Resolution 827 (1993).

^ Resolution Resolution 1674 (2006) Archived 2 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

^ "Security Council passes landmark resolution – world has responsibility to protect people from genocide" (Press release). Oxfam. 28 April 2006. Archived from the original on 12 October 2010.

^ "SECURITY COUNCIL DEMANDS IMMEDIATE AND COMPLETE HALT TO ACTS OF SEXUAL VIOLENCE AGAINST CIVILIANS IN CONFLICT ZONES, UNANIMOUSLY ADOPTING RESOLUTION 1820 (2008) - Meetings Coverage and Press Releases". www.un.org. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

^ "The Crime of Genocide in Domestic Laws and Penal Codes". Website of Prevent Genocide International.

^ William Schabas War crimes and human rights: essays on the death penalty, justice and accountability, Cameron May 2008

ISBN 1-905017-63-4,

ISBN 978-1-905017-63-8. p. 791

^ ab Kurt Jonassohn & Karin Solveig Björnson, Genocide and Gross Human Rights Violations in Comparative Perspective: In Comparative Perspective, Transaction Publishers, 1998,

ISBN 0-7658-0417-4,

ISBN 978-0-7658-0417-4. pp. 133–135

^ M. Hassan Kakar Afghanistan: The Soviet Invasion and the Afghan Response, 1979–1982 University of California press 1995 The Regents of the University of California.

^ M. Hassan Kakar 4. The Story of Genocide in Afghanistan: 13. Genocide Throughout the Country

^ Frank Chalk, Kurt Jonassohn The History and Sociology of Genocide: Analyses and Case Studies, Yale University Press, 1990,

ISBN 0-300-04446-1

^ Court Sentences Mengistu to Death BBC, 26 May 2008.

^ "Code Pénal (France); Article 211-1 – génocide" [Penal Code (France); Article 211-1 – genocide] (in French). Prevent Genocide International. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

^ Daly, Emma (30 June 2003). "Spanish Judge Sends Argentine to Prison on Genocide Charge". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

^ "Profile: Judge Baltasar Garzon". BBC. 7 April 2010. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

^ What is Genocide? Archived 5 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine. McGill Faculty of Law (McGill University) source cites Barbara Harff and Ted Gurr Toward empirical theory of genocides and politicides, International Studies Quarterly, 37:3, 1988

^ Origins and Evolution of the Concept in the Science Encyclopedia by Net Industries. states "Politicide, as [Barbara] Harff and [Ted R.] Gurr define it, refers to the killing of groups of people who are targeted not because of shared ethnic or communal traits, but because of 'their hierarchical position or political opposition to the regime and dominant groups' (p. 360)". But does not give the book title to go with the page number.

^ Staff. There are NO Statutes of Limitations on the Crimes of Genocide! On the website of the American Patriot Friends Network. Cites Barbara Harff and Ted Gurr "Toward empirical theory of genocides and politicides", International Studies Quarterly 37, 3 [1988].

^ Polsby, Daniel D.; Kates, Don B., Jr. (3 November 1997). "OF HOLOCAUSTS AND GUN CONTROL". Washington University Law Quarterly. 75 (Fall): 1237. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 21 February 2011. (cites Harff 1992, see other note)

^ Harff, Barbara (1992). Fein, Helen, ed. "Recognizing Genocides and Politicides". Genocide Watch. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. 27: 37, 38.

^ "DEMOCIDE VERSUS GENOCIDE: WHICH IS WHAT?". www.hawaii.edu. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

^ Adrian Gallagher, Genocide and Its Threat to Contemporary International Order (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013) p. 37.

^ "unhchr.ch". www.unhchr.ch. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

^ (See for example the submission by Agent of the United States, Mr. David Andrews to the ICJ Public Sitting, 11 May 1999 Archived 17 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine.)

^ Oxford English Dictionary: 1944 R. Lemkin Axis Rule in Occupied Europe ix. 79 "By 'genocide' we mean the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group."

^ Oxford English Dictionary "Genocide" citing Sunday Times 21 October 1945

^ Staff. Bosnian genocide suspect extradited, BBC, 2 April 2002

^ "Fifth Section: Case of Jorgic v. Germany: Application no. 74613/01". European Court of Human Rights. 12 July 2007. Retrieved 5 February 2017: see § 47.

^ The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia found in Prosecutor v. Radislav Krstic – Trial Chamber I – Judgment – IT-98-33 (2001) ICTY8 (2 August 2001) that genocide had been committed. (see paragraph 560 for name of group in English on whom the genocide was committed[who?][clarification needed]). It was upheld in Prosecutor v. Radislav Krstic – Appeals Chamber – Judgment – IT-98-33 (2004) ICTY 7 (19 April 2004)

^ "Courte: Serbia failed to prevent genocide, UN court rules". The San Francisco Chronicle. Associated Press. 26 February 2007.

^ ECHR Jorgic v. Germany. § 42 citing Prosecutor v. Krstic, IT-98-33-T, judgment of 2 August 2001, §§ 580

^ ECHR Jorgic v. Germany Judgment, 12 July 2007. § 44 citing Prosecutor v. Kupreskic and Others (IT-95-16-T, judgment of 14 January 2000), § 751. On 14 January 2000, the ICTY ruled in the Prosecutor v. Kupreskic and Others case that the killing of 116 Muslims in order to expel the Muslim population from a village amounted to persecution, not genocide.

^ ICJ press release 2007/8 26 February 2007

^ http://icty.org/x/cases/krajisnik/cis/en/cis_krajisnik_en.pdf

^ Staff (5 November 2009). "Q&A: Karadzic on trial". BBC News. Retrieved 28 January 2010.

^ "Radovan Karadzic, a Bosnian Serb, Gets 40 Years Over Genocide and War Crimes". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

^ "Karadzic sentenced to 40 years for genocide". CNN. Retrieved 2016-03-26.

^ Staff (26 May 2011). "Q&A: Ratko Mladic arrested: Bosnia war crimes suspect held". BBC News. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

^ Bowcott, Owen; Borger, Julian (22 November 2017). "Ratko Mladić convicted of war crimes and genocide at UN tribunal". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

^ These figures need revising they are from the ICTR page which says see www.ictr.org

^ Cambodian Genocide Program, Yale University's MacMillan Center for International and Area Studies

^ "A/RES/57/228B: Khmer Rouge trials" (PDF). United Nations Assistance to the Khmer Rouge Trials (UNAKRT). 22 May 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 July 2007. Retrieved 11 December 2010.

^ ab Doyle, Kevin. "Putting the Khmer Rouge on Trial", Time, 26 July 2007

^ MacKinnon, Ian "Crisis talks to save Khmer Rouge trial", The Guardian, 7 March 2007

^ The Khmer Rouge Trial Task Force Archived 17 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine., Royal Cambodian Government

^ abcd "Case 002". The Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia. 2014. Archived from the original on 23 December 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

^ "Former Khmer Rouge leaders begin genocide trial". BBC News. 30 July 2014. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

^ ab Buncombe, Andrew (11 October 2011). "Judge quits Cambodia genocide tribunal". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 14 October 2011.

^ Munthit, Ker (12 August 2008). "Cambodian tribunal indicts Khmer Rouge jailer". USA Today. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 30 May 2010.

^ "Kaing Guek Eav alias Duch Sentenced to Life Imprisonment by the Supreme Court Chamber". Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia. 3 February 2012. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

^ abcd "Case File No.: 002/19-09-2007-ECCC-OCIJ: Closing Order" (PDF). Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia. 15 September 2010. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

^ ab McKirdy, Euan (9 August 2014). "Top Khmer Rouge leaders found guilty of crimes against humanity, sentenced to life in prison". CNN. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

^ "002/19-09-2007: Decision on immediate appeal against Trial Chamber's order to release the accused Ieng Thirith" (PDF). Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia. 13 December 2011. Retrieved 16 February 2017.

^ "Statement by Carolyn Willson, Minister Counselor for International Legal Affairs, on the Report of the ICC, in the UN General Assembly" (PDF). (123 KB) 23 November 2005

^ Jafari, Jamal and Paul Williams (2005) "Word Games: The UN and Genocide in Darfur" JURIST

^ POWELL DECLARES KILLING IN DARFUR 'GENOCIDE', The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer, 9 September 2004

^ ab "Report of the International Commission of Inquiry on Darfur to the United Nations Secretary-General" (PDF). (1.14 MB), 25 January 2005, at 4

^ "Security Council Resolution 1593 (2005)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2005. (24.8 KB)

^ SECURITY COUNCIL REFERS SITUATION IN DARFUR, SUDAN, TO PROSECUTOR OF INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT, UN Press Release SC/8351, 31 March 2005

^ "Fourth Report of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, to the Security Council pursuant to UNSC 1593 (2005)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 June 2007. (597 KB), Office of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, 14 December 2006.

^ Statement by Mr. Luis Moreno Ocampo, Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, to the United Nations Security Council pursuant to UNSCR 1593 (2005) Archived 13 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine., International Criminal Court, 5 June 2008

^ ICC issues a warrant of arrest for Omar Al Bashir, President of Sudan Archived 27 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine. (ICC-CPI-20090304-PR394), ICC press release, 4 March 2009

^ https://www.icc-cpi.int/CourtRecords/CR2010_04826.PDF

^ Adam Jones (2010), Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction (2nd ed.), p.271. – "'" Next to the Jews in Europe," wrote Alexander Werth', "the biggest single German crime was undoubtedly the extermination by hunger, exposure and in other ways of . . . Russian war prisoners." Yet the murder of at least 3.3 million Soviet POWs is one of the least-known of modern genocides; there is still no full-length book on the subject in English. It also stands as one of the most intensive genocides of all time: "a holocaust that devoured millions," as Catherine Merridale acknowledges. The large majority of POWs, some 2.8 million, were killed in just eight months of 1941–42, a rate of slaughter matched (to my knowledge) only by the 1994 Rwanda genocide."

^ Pair guilty of 'insulting Turkey', BBC News, 11 October 2007.

^ Rubinstein, W. D. (2004). Genocide: a history. Pearson Education. p.7.

ISBN 0-582-50601-8

^ ab M. Hassan Kakar Chapter 4. The Story of Genocide in Afghanistan Footnote 9. Citing Horowitz, quoted in Chalk and Jonassohn, Genocide, 14.

^ M. Hassan Kakar Chapter 4. The Story of Genocide in Afghanistan Footnote 10. Citing For details, see Carlton, War and Ideology.

^ M. Hassan Kakar, Afghanistan: The Soviet Invasion and the Afghan Response, 1979–1982, University of California Press, 1995.

^ ab Gregory Stanton. The 8 Stages of Genocide, Genocide Watch, 1996

^ The FBI has found somewhat similar stages for hate groups.

^ "GenPrev in the News [19 April 2012]". wordpress.com. 19 April 2012. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

^ Dirk Moses Why the Discipline of "Genocide Studies" Has Trouble Explaining How Genocides End?, Social Science Research Council, 22 December 2006

^ Staub, E (1989). The roots of evil: The origins of genocide and other group violence. New York: Cambridge University Press.[page needed]

^ Staub, E. (2011) Overcoming evil: Genocide, violent conflict and terrorism New York: Oxford University Press.[page needed]

^ p. 9. Anderson, Kjell. (2015) Colonialism and Cold Genocide: The Case of West Papua. Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal Vol. 9: Iss. 2: 9–25.

Further reading

Articles

Christopher R. Browning, "The Two Different Ways of Looking at Nazi Murder" (review of Philippe Sands, East West Street: On the Origins of "Genocide" and "Crimes Against Humanity", Knopf, 425 pp., $32.50; and Christian Gerlach, The Extermination of the European Jews, Cambridge University Press, 508 pp., $29.99 [paper]), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXIII, no. 18 (November 24, 2016), pp. 56–58. Discusses Hersch Lauterpacht's legal concept of "crimes against humanity", contrasted with Rafael Lemkin's legal concept of "genocide". All genocides are crimes against humanity, but not all crimes against humanity are genocides; genocides require a higher standard of proof, as they entail intent to destroy a particular group.

The Genocide in Darfur is Not What It Seems Christian Science Monitor

Suharto’s Purge, Indonesia’s Silence. Joshua Oppenheimer for The New York Times, September 29, 2015.- (in Spanish) Aizenstatd, Najman Alexander. "Origen y Evolución del Concepto de Genocidio". Vol. 25 Revista de Derecho de la Universidad Francisco Marroquín 11 (2007).

ISSN 1562-2576 [1]

No Lessons Learned from the Holocaust? Assessing Risks of Genocide and Political Mass Murder since 1955 American Political Science Review. Vol. 97, No. 1. February 2003.- (in Spanish) Marco, Jorge. "Genocidio y Genocide Studies: Definiciones y debates", en: Aróstegui, Julio, Marco, Jorge y Gómez Bravo, Gutmaro (coord.): "De Genocidios, Holocaustos, Exterminios...", Hispania Nova, 10 (2012). Véase [2]

What Really Happened in Rwanda? Christian Davenport and Allan C. Stam.- Reyntjens, F. (2004). "Rwanda, Ten Years On: From Genocide to Dictatorship." African Affairs 103(411): 177–210.

- Brysk, Alison. 1994. "The Politics of Measurement: The Contested Count of the Disappeared in Argentina." Human Rights Quarterly 16: 676–92.

- Davenport, C. and P. Ball (2002). "Views to a Kill: Exploring the Implications of Source Selection in the Case of Guatemalan State Terror, 1977–1996." Journal of Conflict Resolution 46(3): 427–450.

- Krain, M. (1997). "State-Sponsored Mass Murder: A Study of the Onset and Severity of Genocides and Politicides." Journal of Conflict Resolution 41(3): 331–360.

McCormick, Rob (2008). "The United States' Response to Genocide in the Independent State of Croatia, 1941–1945". Genocide Studies and Prevention. 3 (1): 75–98.

Books

Andreopoulos, George J., ed. (1994). Genocide: Conceptual and Historical Dimensions. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-3249-6.- Ball, P., P. Kobrak, and H. Spirer (1999). State Violence in Guatemala, 1960–1996: A Quantitative Reflection. Washington, D.C.: American Association for the Advancement of Science.

- Bloxham, Donald & Moses, A. Dirk [editors]: The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies. [Interdisciplinary Contributions about Past & Present Genocides]. Oxford University Press, second edition 2013.

ISBN 978-0-19-967791-7

Chalk, Frank; Kurt Jonassohn (1990). The History and Sociology of Genocide: Analyses and Case Studies. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-04446-1.

Charny, Israel W. (1 December 1999). Encyclopedia of Genocide. ABC-Clio Inc. ISBN 0-87436-928-2.

Conversi, Daniele (2005). "Genocide, ethnic cleansing, and nationalism". In Delanty, Gerard; Kumar, Krishan. Handbook of Nations and Nationalism. 1. London: Sage Publications. pp. 319–33. ISBN 1-4129-0101-4.- Corradi, Juan, Patricia Weiss Fagen, and Manuel Antonio Garreton, eds. 1992. Fear at the Edge: State Terror and Resistance in Latin America. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Elliot, G. (1972). Twentieth Century Book of the Dead. New York, C. Scribner.

Esparza, Marcia; Henry R. Huttenbach; Daniel Feierstein, eds. (2011). State Violence and Genocide in Latin America: The Cold War Years (Critical Terrorism Studies). Routledge. ISBN 0415664578.

Gellately, Robert; Kiernan, Ben (July 2003). The Specter of Genocide: Mass Murder in Historical Perspective. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521527503.

Goldhagen, Daniel (2009). Worse Than War: Genocide, Eliminationism, and the Ongoing Assault on Humanity. PublicAffairs. p. 672. ISBN 1-58648-769-8.

Harff, Barbara (August 2003). Early Warning of Communal Conflict and Genocide: Linking Empirical Research to International Responses. Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-9840-1.

Hochschild, Adam (1998). King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 0-395-75924-2.

Horowitz, Irving (2001). Taking Lives: Genocide and State Power (5th ed.). Transaction Publishers. ISBN 0-7658-0094-2.

Horvitz, Leslie Alan; Catherwood, Christopher (2011). Encyclopedia of War Crimes & Genocide (Hardcover). 2 (Revised ed.). New York: Facts on File. ISBN 978-0816080830.

ISBN 0816080836

Jonassohn, Kurt; Karin Björnson (1998). Genocide and Gross Human Rights Violations. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 1-56000-314-6.

Jones, Adam (2010). Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-48619-X.

Kelly, Michael J. (2005). Nowhere to Hide: Defeat of the Sovereign Immunity Defense for Crimes of Genocide & the Trials of Slobodan Milosevic and Saddam Hussein. Peter Lang. ISBN 0-8204-7835-0.

Kiernan, Ben (2007). Blood and Soil: A World History of Genocide and Extermination from Sparta to Darfur. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10098-1.

Laban, Alexander (2002). Genocide: An Anthropological Reader. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-22355-X.

Lemarchand, René (1996). Burundi: Ethnic Conflict and Genocide. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56623-1.

Lemkin, Raphael (2008). Axis rule in occupied Europe : laws of occupation, analysis of government, proposals for redress. Clark, N.J: Lawbook Exchange. ISBN 978-1-58477-901-8.- Levene, M. (2005). Genocide in the Age of the Nation State. New York, Palgrave Macmillan.

MacKinnon, Catharine A. (2006). Are Women Human?: And Other International Dialogues. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-02555-5.- Lewy, Guenter (2012). Essays on Genocide and Humanitarian Intervention. University of Utah Press.

ISBN 978-1-60781-168-8. - Mamdani, M. (2001). When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda. Princeton, N.J., Princeton University Press.

Melvin, Jess (2018). The Army and the Indonesian Genocide: Mechanics of Mass Murder. Routledge. ISBN 978-1138574694.

Power, Samantha (2003). "A Problem from Hell": America and the Age of Genocide. Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-06-054164-4.

Rosenfeld, Gavriel D. (1999). "The Politics of Uniqueness: Reflections on the Recent Polemical Turn in Holocaust and Genocide Scholarship". Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 13 (1): 28–61. doi:10.1093/hgs/13.1.28.

Rotberg, Robert I.; Thomas G. Weiss (1996). From Massacres to Genocide: The Media, Public Policy, and Humanitarian Crises. Brookings Institution Press. ISBN 0-8157-7590-3.

Rummel, R.J. (1994). Death by Government: Genocide and Mass Murder in the Twentieth Century. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 1-56000-927-6.

Sagall, Sabby (2013). Final Solutions: Human Nature, Capitalism and Genocide. Pluto Press. p. 309. ISBN 978-0-7453-2653-5.

Sands, Philippe (2016). East West Street : on the origins of "Genocide" and "Crimes Against Humanity". New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-385-35071-6.

Schabas, William A. (2009). Genocide in International Law: The Crime of Crimes (second edition). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52-171900-1.- Schmid, A. P. (1991). Repression, State Terrorism, and Genocide: Conceptual Clarifications. State Organized Terror: The Case of Violent Internal Repression. P. T. Bushnell. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press. 312 p.

Shaw, Martin (2007). What is Genocide?. Cambridge: Polity Press. ISBN 0-7456-3182-7.- Staub, Ervin (1989). The roots of evil: The origins of genocide and other group violence. New York: Cambridge University Press. 978-0521-42214-7

- Staub, Ervin (2011). Overcoming Evil: Genocide, violent conflict and terrorism. New York: Oxford University Press. 978-0-19-538204-4

Sunga, Lyal S. (1997). The Emerging System of International Criminal Law: Developments in Codification and Implementation. Kluwer. ISBN 90-411-0472-0.

Sunga, Lyal S. (1992). Individual Responsibility in International Law for Serious Human Rights Violations. Springer. ISBN 0-7923-1453-0.- Tams, Christian J.; Berster, Lars; Schiffbauer, Björn (2014). Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide: A Commentary. Munich: C.H. Beck.

ISBN 978-3-406-60317-4.

Totten, Samuel; William S. Parsons; Israel W. Charny (2008). Century of Genocide: Critical Essays and Eyewitness Accounts (3rd ed.). Routledge. ISBN 0-415-99085-8.

Valentino, Benjamin A. (2004). Final Solutions: Mass Killing and Genocide in the 20th Century. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-3965-5.- Van den Berghe, P. L. (1990). State Violence and Ethnicity. Niwot, Colo., University of Colorado Press.

Weitz, Eric D. (2003). A Century of Genocide: Utopias of Race and Nation. Princeton University Press. p. 360. ISBN 0-691-12271-7.

Schabas, William A. (2006). Preventing Genocide and Mass Killing: The Challenge for the United Nations (PDF). London: Minority Rights Group International. ISBN 1-904584-37-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 July 2007.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Genocide |

| Look up genocide in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Genocide. |

Documents

Voices of the Holocaust—a learning resource at the British Library

Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (1948) – full text of Genocide Convention- Whitaker Report

8 Stages of Genocide" by Gregory H. Stanton

Research institutes, advocacy groups, and other organizations

- Institute for the Study of Genocide

- International Association of Genocide Scholars

- International Network of Genocide Scholars (INoGS)

United to End Genocide (merger of Save Darfur Coalition and the Genocide Intervention Network)

Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum- Auschwitz Institute for Peace and Reconciliation

- Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Amsterdam, the Netherlands

Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies at the University of Minnesota

Genocide Studies Program at Yale University

Montreal Institute for Genocide Studies at Concordia University

Minorities at Risk Project at the University of Maryland- Budapest Centre for Mass Atrocities Prevention