Indigenous Australians

| Total population | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 798 365 (2016)[1] 3.3% of Australia's population | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Population distribution by state/territory | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Languages | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Several hundred Indigenous Australian languages (many extinct or nearly so), Australian English, Australian Aboriginal English, Torres Strait Creole, Kriol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related ethnic groups | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Papuans, Melanesians | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Indigenous Australians are the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people of Australia, descended from groups that existed in Australia and surrounding islands before British colonisation. The time of arrival of the first Indigenous Australians is a matter of debate among researchers. The earliest conclusively human remains found in Australia are those of Mungo Man LM3 and Mungo Lady, which have been dated to around 50,000 years BP.[2] Recent archaeological evidence from the analysis of charcoal and artefacts revealing human use suggests a date as early as 65,000 BP.[3][4]Luminescence dating has suggested habitation in Arnhem Land as far back as 60,000 years BP.[5] Genetic research has inferred a date of habitation as early as 80,000 years BP.

Other estimates have ranged up to 100,000 years[6] and 125,000 years ago.[7]

Although there are a number of commonalities between Indigenous Aboriginal Australians, there is also a great diversity among different Indigenous communities and societies in Australia, each with its own mixture of cultures, customs and languages. In present-day Australia these groups are further divided into local communities.[8] At the time of initial European settlement, over 250 languages were spoken; it is currently estimated that 120 to 145 of these remain in use, but only 13 of these are not considered endangered.[9][10] Aboriginal people today mostly speak English, with Aboriginal phrases and words being added to create Australian Aboriginal English (which also has a tangible influence of Indigenous languages in the phonology and grammatical structure). The population of Indigenous Australians at the time of permanent European settlement is contentious and has been estimated at between 318,000[11] and 1,000,000[12] with the distribution being similar to that of the current Australian population, the majority living in the south-east, centred along the Murray River.[13] A population collapse principally from disease followed European invasion[14][15] beginning with a smallpox epidemic spreading three years after the arrival of Europeans. Massacres and war by British settlers also contributed to depopulation.[16][17] The characterisation of this violence as genocide is controversial and disputed.[18]

Since 1995, the Australian Aboriginal Flag and the Torres Strait Islander Flag have been among the official flags of Australia.

Contents

1 Indigenous Australia

1.1 Terminology

1.2 Regional groups

1.3 Torres Strait Islanders

1.4 The terms "black" and "blackfella"

2 History

2.1 Migration to Australia

2.2 Before European contact

2.3 British colonisation

2.4 Frontier Wars

2.5 Early 20th century

2.6 Late 20th century to present

3 Society, language, culture, and technology

3.1 Languages

3.2 Belief systems

3.3 Music

3.4 Art

3.5 Literature

3.6 Film

3.7 Traditional recreation and sport

3.8 Technology

4 Genetics

5 Population

5.1 Definition

5.2 Inclusion in the National Census

5.3 Demographics

5.3.1 State distribution and identification growth rate

5.3.2 Urbanisation rate

5.3.3 Intermarriage rate

6 Groups and communities

6.1 Tasmania

7 Contemporary issues

7.1 Identity

7.2 Stolen Generations

7.3 Political representation

7.3.1 Australian politicians of Indigenous ancestry

7.4 Age characteristics

7.5 Life expectancy

7.6 Education

7.7 Employment

7.8 Health

7.9 Crime

7.10 Substance abuse

7.11 Native title and sovereignty

7.12 Stolen wages

7.13 Cross-cultural miscommunication

8 Prominent Indigenous Australians

9 See also

10 Notes

10.1 Citations

11 Sources

12 External links

Indigenous Australia

The Australian Aboriginal Flag

Terminology

The word aboriginal has been in the English language since at least the 16th century to mean, "first or earliest known, indigenous". It comes from the Latin word aborigines, derived from ab (from) and origo (origin, beginning).[19] The word was used in Australia to describe its indigenous peoples as early as 1789. It soon became capitalised and employed as the common name to refer to all Indigenous Australians.

While the term Indigenous Australians, has grown since the 1980s[20] to include to be more inclusive of Torres Strait Islander people, many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples dislike it, feeling that it is too generic and removes their identity. Being more specific, for example naming the language group, is considered best practice and most respectful. Terms that are considered disrespectful include Aborigine and ATSI (acronym for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander)[21][22]

Regional groups

The broad term Aboriginal Australians includes many regional groups that often identify under names from local Indigenous languages. These include:

Men and boys playing a game of gorri, 1922

Murrawarri people – see Murrawarri Republic and Murawari language;

Koori (or Koorie) in New South Wales and Victoria (Victorian Aborigines);

Ngunnawal in the Australian Capital Territory and surrounding areas of New South Wales;- Goorie in South East Queensland and some parts of northern New South Wales;

Murrdi in Southwest and Central Queensland;

Murri used in Queensland and northern New South Wales where specific collective names (such as Gorrie or Murrdi) are not used;

Nyungar in southern Western Australia;

Yamatji in central Western Australia;

Wangai in the Western Australian Goldfields;

Nunga in southern South Australia;

Anangu in northern South Australia, and neighbouring parts of Western Australia and Northern Territory;

Yapa in western central Northern Territory;

Arrernte in central Australia;

Yolngu in eastern Arnhem Land (NT);

Bininj in Western Arnhem Land (NT);

Tiwi on Tiwi Islands off Arnhem Land.

Anindilyakwa on Groote Eylandt off Arnhem Land;

Palawah (or Pallawah) in Tasmania.

Men from Bathurst Island, 1939

These larger groups may be further subdivided; for example, Anangu (meaning a person from Australia's central desert region) recognises localised subdivisions such as Pitjantjatjara, Yankunytjatjara, Ngaanyatjarra, Luritja and Antikirinya. It is estimated that before the arrival of British settlers, the population of Indigenous Australians was approximately 318,000–750,000 across the continent.[12]

Torres Strait Islanders

Map of Torres Strait Islands

The Torres Strait Islanders possess a heritage and cultural history distinct from Aboriginal traditions. The eastern Torres Strait Islanders in particular are related to the Papuan peoples of New Guinea, and speak a Papuan language.[23] Accordingly, they are not generally included under the designation "Aboriginal Australians". This has been another factor in the promotion of the more inclusive term "Indigenous Australians". Six percent of Indigenous Australians identify themselves fully as Torres Strait Islanders. A further 4% of Indigenous Australians identify themselves as having both Torres Strait Islander and Aboriginal heritage.[24]

The Torres Strait Islands comprise over 100 islands[25] which were annexed by Queensland in 1879.[25] Many Indigenous organisations incorporate the phrase "Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander" to highlight the distinctiveness and importance of Torres Strait Islanders in Australia's Indigenous population.

Eddie Mabo was from "Mer" or Murray Island in the Torres Strait, which the famous Mabo decision of 1992 involved.[25]

The terms "black" and "blackfella"

The term "black" has been used to refer to Indigenous Australians since European settlement.[26] While originally related to skin colour, the term is used today to indicate Aboriginal heritage or culture in general and refers to any people of such heritage regardless of their level of skin pigmentation.[27]

In the 1970s, many Aboriginal activists, such as Gary Foley, proudly embraced the term "black", and writer Kevin Gilbert's ground-breaking book from the time was entitled Living Black. The book included interviews with several members of the Aboriginal community, including Robert Jabanungga, reflecting on contemporary Aboriginal culture. A less formal term, used by Indigenous Australians themselves and not normally derogatory, is "blackfellas", as distinguished from "whitefellas".

History

Migration to Australia

Artwork depicting the first contact that was made with the Gweagal Aboriginal people and Captain James Cook and his crew on the shores of the Kurnell Peninsula, New South Wales

Several settlements of humans in Australia have been dated around 49,000 years ago.[28][29]Luminescence dating of sediments surrounding stone artefacts at Madjedbebe, a rock shelter in northern Australia, indicates human activity at 65,000 years BP.[30] Genetic studies appear to support an arrival date of 50-70,000 years ago.[31]

The earliest anatomically modern human remains found in Australia (and outside of Africa) are those of Mungo Man; they have been dated at 42,000 years old.[2][32] The initial comparison of the mitochondrial DNA from the skeleton known as Lake Mungo 3 (LM3) with that of ancient and modern Aborigines indicated that Mungo Man is not related to Australian Aborigines.[33] However, these findings have been met with a general lack of acceptance in scientific communities.[citation needed] The sequence has been criticised as there has been no independent testing, and it has been suggested that the results may be due to posthumous modification and thermal degradation of the DNA.[34][35][36][37] Although the contested results seem to indicate that Mungo Man may have been an extinct subspecies that diverged before the most recent common ancestor of contemporary humans,[33] the administrative body for the Mungo National Park believes that present-day local Aborigines are descended from the Lake Mungo remains.[38] Independent DNA testing is unlikely as the Indigenous custodians are not expected to allow further invasive investigations.[39]

It is generally believed that Aboriginal people are the descendants of a single migration into the continent, a people that split from the first modern human populations to leave Africa 64,000 to 75,000 years ago,[40] although a minority proposed an earlier theory that there were three waves of migration,[41] most likely island hopping by boat during periods of low sea levels (see Prehistory of Australia). Recent work with mitochondrial DNA suggests a founder population of between 1,000 and 3,000 women to produce the genetic diversity observed, which suggests "that initial colonization of the continent would have required deliberate organized sea travel, involving hundreds of people".[42] Aboriginal people seem to have lived a long time in the same environment as the now extinct Australian megafauna.[43]

Genetically, while Indigenous Australians are most closely related to Melanesian and Papuan people, there is also a Eurasian component that could indicate South Asian admixture or more recent European influence.[44][45] Research indicates a single founding Sahul group with subsequent isolation between regional populations which were relatively unaffected by later migrations from the Asian mainland, which may have introduced the dingo 4–5,000 years ago. The research also suggests a divergence from the Papuan people of New Guinea and Mamanwa people of the Philippines about 32,000 years ago with a rapid population expansion about 5,000 years ago.[45] A 2011 genetic study found evidence that the Aboriginal, Papuan and Mamanwa peoples carry some of the genes associated with the Denisovan peoples of Asia, (not found amongst populations in mainland Asia) suggesting that modern and archaic humans interbred in Asia approximately 44,000 years ago, before Australia separated from Papua New Guinea and the migration to Australia.[46][47] A 2012 paper reports that there is also evidence of a substantial genetic flow from India to northern Australia estimated at slightly over four thousand years ago, a time when changes in tool technology and food processing appear in the Australian archaeological record, suggesting that these may be related.[48]

Before European contact

Aboriginal people mainly lived as foragers and hunter-gatherers, hunting and foraging for food from the land. Although Aboriginal society was generally mobile, or semi-nomadic, moving according to the changing food availability found across different areas as seasons changed, the mode of life and material cultures varied greatly from region to region, and there were permanent settlements[49] and agriculture[50] in some areas. The greatest population density was to be found in the southern and eastern regions of the continent, the River Murray valley in particular.

There is evidence that some Aboriginal populations in northern Australia regularly traded with Makassan fishermen from Indonesia before the arrival of Europeans.[51][52]

At the time of first European contact, it is generally estimated that the pre-1788 population was 314,000, while recent archaeological finds suggest that a population of 500,000 to 750,000 could have been sustained, with some ecologists estimating that a population of up to a million or even two million people was possible.[12][53][a]

More recent work suggests that Aboriginal populations exceeded 1.2 million 500 years ago, but may have fallen somewhat with the introduction of disease pathogens from Eurasia in the last 500 years.[42]

The population was split into 250 individual nations, many of which were in alliance with one another, and within each nation there existed separate, often related clans, from as few as 5 or 6 to as many as 30 or 40. Each nation had its own language, and a few had several.[citation needed]

All evidence suggests that the section of the Australian continent now occupied by Queensland was the single most densely populated area of pre-contact Australia.[citation needed]

| State/territory | 1930-estimated share of population | 1988-estimated share of population | Distribution of trad. tribal land |

|---|---|---|---|

| Queensland | 38.2% | 37.9% | 34.2% |

| Western Australia | 19.7% | 20.2% | 22.1% |

| Northern Territory | 15.9% | 12.6% | 17.2% |

| New South Wales | 15.3% | 18.9% | 10.3% |

| Victoria | 4.8% | 5.7% | 5.7% |

| South Australia | 4.8% | 4.0% | 8.6% |

| Tasmania | 1.4% | 0.6% | 2.0% |

The evidence based on two independent sources thus suggests that the territory of Queensland had a pre-contact Indigenous population density twice that of New South Wales, at least six times that of Victoria and more than twenty times that of Tasmania.[dubious ] Equally, there are signs that the population density of Indigenous Australia was comparatively higher in the north-eastern sections of New South Wales, and along the northern coast from the Gulf of Carpentaria and westward including certain sections of Northern Territory and Western Australia. (See also Horton's Map of Aboriginal Australia.[55])

British colonisation

Wurundjeri people at the signing of Batman's Treaty, 1835

British colonisation of Australia began with the arrival of the First Fleet in Botany Bay, New South Wales, in 1788. Settlements were subsequently established in Tasmania (1803), Victoria (1803), Queensland (1824), the Northern Territory (1824), Western Australia (1826), and South Australia (1836). Australia was the exception to British imperial colonization practices, in that no treaty was drawn up setting out terms of agreement between the settlers and native proprietors, as was the case in North America, and New Zealand.[56] Many of the men on the First Fleet had had military experience among Indian tribes in North America, and tended to attribute to the aborigines alien and misleading systems or concepts like chieftainship and tribe with which they had become acquainted in the northern hemisphere.[57]

One immediate consequence was a series of epidemics of European diseases such as measles, smallpox and tuberculosis. In the 19th century, smallpox was the principal cause of Aboriginal deaths, and vaccinations of the "native inhabitants" had begun in earnest by the 1840s.[15] This smallpox epidemic in 1789 is estimated to have killed up to 90% of the Darug people. The cause of the outbreak is disputed. Some scholars have attributed it to European settlers,[58][59] but it is also argued that Macassan fishermen from South Sulawesi and nearby islands may have introduced smallpox to Australia before the arrival of Europeans.[60] A third suggestion is that the outbreak was caused by contact with members of the First Fleet.[61] A fourth theory is that the epidemic was of chickenpox, not smallpox, carried by members of the First Fleet, and to which the Aborigines also had no immunity.[62][63][64][65]

Another consequence of British colonisation was European seizure of land and water resources, with the decimation of kangaroo and other indigenous foodstuffs which continued throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries as rural lands were converted for sheep and cattle grazing.[citation needed] Settlers also participated in the rape and forcible prostitution of Aboriginal women.[66] Despite this a number of Europeans, including convicts, formed favourable impressions of Aboriginal life through living with Aboriginal Groups.[67]

In 1834 there occurred the first recorded use of Aboriginal trackers, who proved very adept at navigating their way through the Australian landscape and finding people.[68]

During the 1860s, Tasmanian Aboriginal skulls were particularly sought internationally for studies into craniofacial anthropometry. The skeleton of Truganini, a Tasmanian Aboriginal who died in 1876, was exhumed within two years of her death despite her pleas to the contrary by the Royal Society of Tasmania, and later placed on display. Campaigns continue to have Aboriginal body parts returned to Australia for burial; Truganini's body was returned in 1976 and cremated, and her ashes were scattered according to her wishes.

In 1868, a group of mostly Aboriginal cricketers toured England, becoming the first Australian cricket team to travel overseas.[69]

Frontier Wars

As part of the colonisation process, there were many small scale conflicts between colonists and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders across the continent. Since the 1970s there has been more systematic research into this conflict which is described as the Australian frontier wars. In Queensland, the killing of Aboriginal peoples was largely perpetrated by civilian "hunting" parties and the Native Police, armed groups of Aboriginal men who were recruited at gunpoint and led by colonialist to eliminate Aboriginal resistance.[70] There is evidence that massacres of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, which began with arrival of British colonists, continued until the 1930s. Researchers at the University of Newcastle have begun mapping the massacres.[71] So far they have mapped almost 500 places where massacres happened, with 12,361 Aboriginal people killed and 204 Colonists killed.[72]

Estimating the total number of deaths during the frontier wars is difficult due to lack of records and the fact that many massacres of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander were kept secret.[71] It is often quoted that 20,000 Aboriginal Australians and 2000 colonists died in the frontier wars,[73] however recent research has shown that a minimum of 65,000 Aboriginal peoples may have been killed in Queensland alone.[74] There has been arguments over whether deaths of Aboriginal peoples, particularly in Tasmania, as well as the forcible removal of children from Aboriginal communities, constitutes genocide.[75][76][77] Many place names in Australia mark places of frontier massacres, for example Murdering Gulley in Newcastle.[78] Place names also reveal discrimination, such as Mount Jim Crow in Rockhampton, Queensland, as well as racist policies, like Brisbane's Boundary Streets which used to indicate boundaries where Aboriginal people were not allowed to cross during certain times of the day.[79] There is ongoing discussion about changing many of these names.[80][81] From 1810, Aboriginal peoples were moved onto mission stations, run by churches and the state.[82] While they provided food and shelter, their purpose was to "civilise" Aboriginal communities by teaching western values. After this period of protectionist policies that aimed to segregate and control Aboriginal populations, in 1937 the Commonwealth government agreed to move towards assimilation policies. These policies aimed to integrate Aboriginal persons who were "not of full blood" into the white community in an effort to eliminate the "Aboriginal problem". As part of this, there was an increase in the number of children forcibly removed from their homes and placed with white people, either in institutions or foster homes.[83]

During this time, many Aboriginal people were victims of slavery by colonists alongside Pacific Islander peoples who were kidnapped from their homes. Between 1860 and 1970, under the guise of protectionist policies, people, including children as young as 12, were forced to work on properties where they worked under horrific conditions and most did not receive any wages.[84] In the pearling industry, Aboriginal peoples were bought for about 5 pounds, with pregnant Aboriginal women "prized because their lungs were believed to have greater air capacity"[85] Aboriginal prisoners in the Aboriginal-only prison on Rottnest Island, many of whom were there on trumped up charges, were chained up and forced to work.[86] In 1971, 373 Aboriginal men were found buried in unmarked graves on the island.[87] Up until June 2018, the former prison was being used as holiday accommodation.[88] There has always been Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander resistance, from the arrival of colonists through to now.[89] In 1938, over 100 Aboriginal peoples protested one of the first Australia Day celebrations by gathering for an "Aborigines Conference" in Sydney and marking the day as the "Day of Protest and Mourning".[90] In 1963 the Yolngu people of Yirrkala in Arnhem Land sent two bark petitions to the Australian government to protest the granting of mining rights on their lands. The Yirrkala Bark petitions were traditional Aboriginal documents to be recognised under Commonwealth law.[91] On Australia day in 1972, 34 years after the first "Day of Protest and Mourning", Indigenous activists set up the Aboriginal Tent Embassy on the lawn of Old Parliament House to protest the state of Aboriginal Australian land rights. The Tent Embassy was given heritage status in 1995, and celebrated its 40th anniversary in 2012,[92] making it the longest, unanswered protest camp in the world.[93]

Early 20th century

By 1900, the recorded Indigenous population of Australia had declined to approximately 93,000.[11] However, this was only a partial count as both Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders were poorly covered, with desert Aboriginal peoples not counted at all until the 1930s.[94] The last uncontacted tribe left the Gibson Desert in 1984.[95] During the first half of the twentieth century, many Indigenous Australians worked as stockmen on sheep stations and cattle stations for extremely low wages. The Indigenous population continued to decline, reaching a low of 74,000 in 1933 before numbers began to recover. By 1995, population numbers had reached pre-colonisation levels, and in 2010 there were around 563,000 Indigenous Australians.[53]

Although, as British subjects, all Indigenous Australians were nominally entitled to vote, generally only those who merged into mainstream society did so. Only Western Australia and Queensland specifically excluded Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people from the electoral rolls. Despite the Commonwealth Franchise Act 1902, which excluded "Aboriginal natives of Australia, Asia, Africa and Pacific Islands except New Zealand" from voting unless they were on the roll before 1901, South Australia insisted that all voters enfranchised within its borders would remain eligible to vote in the Commonwealth, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people continued to be added to their rolls, albeit haphazardly.[94]

Aboriginal women, Northern Territory, 1928. Photo taken by Herbert Basedow.

Despite efforts to bar their enlistment, over 1,000 Indigenous Australians fought for Australia in the First World War.[96]

1934 saw the first appeal to the High Court by an Aboriginal Australian, and it succeeded. Dhakiyarr was found to have been wrongly convicted of the murder of a white policeman, for which he had been sentenced to death; the case focused national attention on Aboriginal rights issues. Dhakiyarr disappeared upon release.[97][98] In 1938, the 150th anniversary of the arrival of the British First Fleet was marked as a Day of Mourning and Protest at an Aboriginal meeting in Sydney, and has since become marked around Australia as "Invasion Day" or "Survival Day" by Aboriginal protesters and their supporters.[99]

Hundreds of Indigenous Australians served in the Australian armed forces during World War Two – including with the Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion and The Northern Territory Special Reconnaissance Unit, which were established to guard Australia's North against the threat of Japanese invasion.[100] However, most were denied pension rights and military allotments, except in Victoria, where each case was judged individually, without a blanket denial of rights accruing from their service.[c]

Late 20th century to present

The 1960s was a pivotal decade in the assertion of Aboriginal rights and a time of growing collaboration between Aboriginal activists and white Australian activists.[102] In 1962, Commonwealth legislation specifically gave Aboriginal people the right to vote in Commonwealth elections.[103] A group of University of Sydney students organised a bus tour of western and coastal New South Wales towns in 1965 to raise awareness of the state of Aboriginal health and living conditions. This Freedom Ride also aimed to highlight the social discrimination faced by Aboriginal people and encourage Aboriginal people themselves to resist discrimination.[104] In 1966, Vincent Lingiari led a famous walk-off of Indigenous employees of Wave Hill Station in protest against poor pay and conditions[105] (later the subject of the Paul Kelly song "From Little Things Big Things Grow").[106] The landmark 1967 referendum called by Prime Minister Harold Holt allowed the Commonwealth to make laws with respect to Aboriginal people by modifying section 51(xxvi) of the Constitution, and for Aboriginal people to be included when the country does a count to determine electoral representation by repealing section 127. The referendum passed with 90.77% voter support.[107]

In the controversial 1971 Gove land rights case, Justice Blackburn ruled that Australia had been terra nullius before British settlement, and that no concept of native title existed in Australian law. Following the 1973 Woodward commission enquiry, in 1976 the Australian federal government under Gough Whitlam enacted the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 to recognise Aboriginal Australians' system of land rights in the Northern Territory. In 1985, the Australian government returned ownership of Uluru (Ayers Rock) to the Pitjantjatjara Aboriginal people. In 1992, the High Court of Australia reversed Justice Blackburn's ruling and handed down its decision in the Mabo Case, declaring the previous legal concept of terra nullius to be invalid and confirming the existence of native title in Australia.

Indigenous Australians began to serve in political office from the 1970s. In 1971, Neville Bonner joined the Australian Senate as a Senator for Queensland for the Liberal Party, becoming the first Indigenous Australian in the Federal Parliament. A year later, the Aboriginal Tent Embassy was established on the steps of Parliament House in Canberra. In 1976, Sir Douglas Nicholls was appointed as the 28th Governor of South Australia, the first Aboriginal person appointed to vice-regal office.[108] In the general election of 2010, Ken Wyatt of the Liberal Party became the first Indigenous Australian elected to the Australian House of Representatives. In the general election of 2016, Linda Burney of the Australian Labor Party became the second Indigenous Australian, and the first Indigenous Australian woman, elected to the Australian House of Representatives.[109] She was immediately appointed Shadow Minister for Human Services.[110]

In sport Evonne Goolagong Cawley became the world number-one ranked tennis player in 1971 and won 14 Grand Slam titles during her career. In 1973 Arthur Beetson became the first Indigenous Australian to captain his country in any sport when he first led the Australian National Rugby League team, the Kangaroos.[111] In 1982, Mark Ella became Captain of the Australian National Rugby Union Team, the Wallabies.[112] In 2000, Aboriginal sprinter Cathy Freeman lit the Olympic flame at the opening ceremony of the 2000 Summer Olympics in Sydney, and went on to win the 400 metres at the Games.

In 1984, a group of Pintupi people who were living a traditional hunter-gatherer desert-dwelling life were tracked down in the Gibson Desert in Western Australia and brought in to a settlement. They are believed to have been the last uncontacted tribe in Australia.[113]

Picture of Albert Namatjira at the Albert Namatjira Gallery, Alice Springs. Aboriginal art and artists became increasingly prominent in Australian cultural life during the second half of the 20th century.

Australian tennis player Evonne Goolagong

Reconciliation between non-Indigenous and Indigenous Australians became a significant issue in Australian politics in the late 20th century. In 1991, the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation was established by the federal government to facilitate reconciliation. In 1998, a Constitutional Convention which selected a Republican model for a referendum included just six Indigenous participants, leading Monarchist delegate Neville Bonner to end his contribution to the Convention with his Jagera tribal "Sorry Chant" in sadness at the low number of Indigenous representatives. The republican model, as well as a proposal for a new Constitutional preamble which would have included the "honouring" of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, was put to referendum but did not succeed.[114] In 1999, the Australian Parliament passed a Motion of Reconciliation drafted by Prime Minister John Howard in consultation with Aboriginal Senator Aden Ridgeway naming mistreatment of Indigenous Australians as the most "blemished chapter in our national history", although Howard refused to offer any formal apology.[115] In 2001, the Federal Government dedicated Reconciliation Place in Canberra. On 13 February 2008, Prime Minister Kevin Rudd reversed Howard's decision and issued a public apology to members of the Stolen Generations on behalf of the Australian Government. In 2010, the federal government appointed a panel comprising Indigenous leaders, other legal experts and some members of parliament (including Ken Wyatt) to provide advice on how best to recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the federal Constitution. The panel's recommendations, reported to the federal government in January 2012,[116] included deletion of provisions of the Constitution referencing race (Section 25 and Section 51(xxvi)), and new provisions on meaningful recognition and further protection from discrimination.[d] Subsequently, a proposed referendum on Constitutional recognition of Indigenous Australians was ultimately abandoned in 2013.

During the same period, the federal government enacted a number of significant, but controversial, policy initiatives in relation to Indigenous Australians. A representative body, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission, was set up in 1990, but was abolished by the Australian Government in 2004 amidst allegations of corruption.[117] The Northern Territory National Emergency Response (also known as the Northern Territory Intervention) was launched in 2007 by the government of Prime Minister John Howard, in response to the Little Children are Sacred Report into allegations of child abuse among Indigenous communities. The government banned alcohol in prescribed communities in the Territory; quarantined a percentage of welfare payments for essential goods purchasing; dispatched additional police and medical personnel to the region; and suspended the permit system for access to Indigenous communities.[118] In addition to these measures, the army were released into communities[119] and there were increased police powers, which were later further increased with the so-called "paperless arrests" legislation.[120]

In 2010, United Nations Special Rapporteur James Anaya found the Emergency Response to be racially discriminatory, and said that aspects of it represented a limitation on "individual autonomy".[121][122] These findings were criticised by the government's Indigenous Affairs Minister Jenny Macklin, the Opposition and Indigenous leaders like Warren Mundine and Bess Price.[123][124] In 2011, the Australian government enacted legislation to implement the Stronger Futures policy, which is intended to address key issues that exist within Aboriginal communities of the Northern Territory such as unemployment, school attendance and enrolment, alcohol abuse, community safety and child protection, food security and housing and land reforms. The policy has been criticised by organisations such as Amnesty International and other groups, including on the basis that it maintains "racially-discriminatory" elements of the Northern Territory Emergency Response Act and continue control of the Australian Government over "Aboriginal people and their lands".[125]

Society, language, culture, and technology

Aboriginal dancers in 1981

There are a large number of tribal divisions and language groups in Aboriginal Australia, and, correspondingly, a wide variety of diversity exists within cultural practices. However, there are some similarities between cultures.

Languages

According to the 2005 National Indigenous Languages Survey (NILS), at the time the Australian continent was colonised, there were around 250 different Indigenous languages, with the larger language groups each having up to 100 related dialects. Some of these languages were only ever spoken by perhaps 50 to 100 people. Indigenous languages are divided into language groups with from ten to twenty-four language families identified.[9] It is currently estimated that up to 145 Indigenous languages remain in use, of which fewer than 20 are considered to be strong in the sense that they are still spoken by all age groups.[9][126] All but 13 Indigenous languages are considered to be endangered.[10] Several extinct Indigenous languages are being reconstructed. For example, the last fluent speaker of the Ngarrindjeri language died in the late 1960s; using recordings and written records as a guide, a Ngarrindjeri dictionary was published in 2009,[127] and the Ngarrindjeri language is today being spoken in complete sentences.[9]

Linguists classify many of the mainland Australian languages into one large group, the Pama–Nyungan languages. The rest are sometimes lumped under the term "non-Pama–Nyungan". The Pama–Nyungan languages comprise the majority, covering most of Australia, and are generally thought to be a family of related languages. In the north, stretching from the Western Kimberley to the Gulf of Carpentaria, are found a number of non-Pama–Nyungan groups of languages which have not been shown to be related to the Pama–Nyungan family nor to each other.[128] While it has sometimes proven difficult to work out familial relationships within the Pama–Nyungan language family, many Australian linguists feel there has been substantial success.[129] Against this, some linguists, such as R. M. W. Dixon, suggest that the Pama–Nyungan group – and indeed the entire Australian linguistic area – is rather a sprachbund, or group of languages having very long and intimate contact, rather than a genetic language family.[130]

It has been suggested that, given their long presence in Australia, Aboriginal languages form one specific sub-grouping. The position of Tasmanian languages is unknown, and it is also unknown whether they comprised one or more than one specific language family.

Belief systems

Depiction of a corroboree by 19th century Indigenous activist William Barak

Religious demography among Indigenous Australians is not conclusive because the methodology of the census is not always well suited to obtaining accurate information on Aboriginal people.[131] In the 2006 census, 73% of the Indigenous population reported an affiliation with a Christian denomination, 24% reported no religious affiliation and 1% reported affiliation with an Australian Aboriginal traditional religion.[132] A small minority of Aborigines are followers of Islam as a result of intermarriage with "Afghan" camel drivers brought to Australia in the late 19th and early 20th century.[133]

Aboriginal people traditionally adhered to animist spiritual frameworks. Within Aboriginal belief systems, a formative epoch known as "the Dreamtime" or "the Dreaming" stretches back into the distant past when the creator ancestors known as the First Peoples travelled across the land, and naming as they went.[134] Indigenous Australia's oral tradition and religious values are based upon reverence for the land and a belief in this Dreamtime.

The Dreaming is at once both the ancient time of creation and the present-day reality of Dreaming. There were a great many different groups, each with its own individual culture, belief structure, and language. These cultures overlapped to a greater or lesser extent, and evolved over time. Major ancestral spirits include the Rainbow Serpent, Baiame, Dirawong and Bunjil.

Traditional healers (known as Ngangkari in the Western desert areas of Central Australia) were highly respected men and women who not only acted as healers or doctors, but were generally also custodians of important Dreamtime stories.[135]

Music

A didgeridoo player

Music has formed an integral part of the social, cultural and ceremonial observances of people through the millennia of their individual and collective histories to the present day, and has existed for 50,000 years.[136][137][138][139]

The various Indigenous Australian communities developed unique musical instruments and folk styles. The didgeridoo, which is widely thought to be a stereotypical instrument of Aboriginal people, was traditionally played by people of only the eastern Kimberley region and Arnhem Land (such as the Yolngu), and then by only the men.[140]

Around 1950, the first research into Aboriginal music was undertaken by the anthropologist Adolphus Elkin, who recorded Aboriginal music in Arnhem Land.[141]

Hip hop music is helping preserve indigenous languages.[142]

At the Sydney 2000 Olympics, Christine Anu sang the song "My Island Home" at the Closing Ceremony.[citation needed]

Art

@media all and (max-width:720px).mw-parser-output .tmulti>.thumbinnerwidth:100%!important;max-width:none!important.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsinglefloat:none!important;max-width:none!important;width:100%!important;text-align:center

Bradshaw rock paintings in the Kimberley region of Western Australia

Arnhem Land artist at work

Aboriginal Memorial, National Gallery of Australia

Australia has a tradition of Aboriginal art which is thousands of years old, the best known forms being rock art and bark painting. Evidence of Aboriginal art in Australia can be traced back at least 30,000 years.[143] Examples of ancient Aboriginal rock artworks can be found throughout the continent – notably in national parks such as those of the UNESCO listed sites at Uluru and Kakadu National Park in the Northern Territory, but also within protected parks in urban areas such as at Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park in Sydney.[144][145][146] The Sydney rock engravings are approximately 5000 to 200 years old. Murujuga in Western Australia has the Friends of Australian Rock Art have advocated its preservation, and the numerous engravings there were heritage listed in 2007.[147]

In terms of age and abundance, cave art in Australia is comparable to that of Lascaux and Altamira in Europe,[148] and Aboriginal art is believed to be the oldest continuing tradition of art in the world.[149] There are three major regional styles: the geometric style found in Central Australia, Tasmania, the Kimberley and Victoria known for its concentric circles, arcs and dots; the simple figurative style found in Queensland and the complex figurative style found in Arnhem Land and the Kimberley which includes X-Ray art, Gwian Gwian (Bradshaw) and Wunjina. These designs generally carry significance linked to the spirituality of the Dreamtime.[143] Paintings were usually created in earthy colours, from paint made from ochre. Such ochres were also used to paint their bodies for ceremonial purposes.

Modern Aboriginal artists continue the tradition, using modern materials in their artworks. Several styles of Aboriginal art have developed in modern times, including the watercolour paintings of the Hermannsburg School, and the acrylic Papunya Tula "dot art" movement. William Barak (c.1824–1903) was one of the last traditionally educated of the Wurundjeri-willam, people who come from the district now incorporating the city of Melbourne. He remains notable for his artworks which recorded traditional Aboriginal ways for the education of Westerners (which remain on permanent exhibition at the Ian Potter Centre of the National Gallery of Victoria and at the Ballarat Fine Art Gallery. Margaret Preston (1875–1963) was among the early non-indigenous painters to incorporate Aboriginal influences in her works. Albert Namatjira (1902–1959) is one of the most famous Australian artists and an Arrernte man. His landscapes inspired the Hermannsburg School of art. The works of Elizabeth Durack are notable for their fusion of Western and indigenous influences. Since the 1970s, indigenous artists have employed the use of acrylic paints – with styles such as that of the Western Desert Art Movement becoming globally renowned 20th-century art movements.

The National Gallery of Australia exhibits a great many indigenous art works, including those of the Torres Strait Islands who are known for their traditional sculpture and headgear.[150]

Literature

David Unaipon, the first Aboriginal published author

By 1788, Indigenous Australians had not developed a system of writing[citation needed], so the first literary accounts of Aborigines come from the journals of early European explorers, which contain descriptions of first contact, both violent and friendly. Early accounts by Dutch explorers and the English buccaneer William Dampier wrote of the "natives of New Holland" as being "barbarous savages", but by the time of Captain James Cook and First Fleet marine Watkin Tench (the era of Jean-Jacques Rousseau), accounts of Aborigines were more sympathetic and romantic: "these people may truly be said to be in the pure state of nature, and may appear to some to be the most wretched upon the earth; but in reality they are far happier than ... we Europeans", wrote Cook in his journal on 23 August 1770.

Letters written by early Aboriginal leaders like Bennelong and Sir Douglas Nicholls are retained as treasures of Australian literature, as is the historic Yirrkala bark petitions of 1963 which is the first traditional Aboriginal document recognised by the Australian Parliament.[151]David Unaipon (1872–1967) is credited as providing the first accounts of Aboriginal mythology written by an Aboriginal: Legendary Tales of the Aborigines; he is known as the first Aboriginal author. Oodgeroo Noonuccal (1920–1995) was a famous Aboriginal poet, writer and rights activist credited with publishing the first Aboriginal book of verse: We Are Going (1964).[152]Sally Morgan's novel My Place was considered a breakthrough memoir in terms of bringing indigenous stories to wider notice. Leading Aboriginal activists Marcia Langton (First Australians, 2008) and Noel Pearson ("Up From the Mission", 2009) are active contemporary contributors to Australian literature.

The voices of Indigenous Australians are being increasingly noticed and include the playwright Jack Davis and Kevin Gilbert. Writers coming to prominence in the 21st century include Alexis Wright, Kim Scott, twice winner of the Miles Franklin award, Tara June Winch, in poetry Yvette Holt and in popular fiction Anita Heiss. Australian Aboriginal poetry – ranging from sacred to everyday – is found throughout the continent.[e]

Mathinna, painted in 1842 by convict Thomas Bock, inspired Richard Flanagan to write Wanting (2008).

Many notable works have been written by non-indigenous Australians on Aboriginal themes. Examples include the poems of Judith Wright; The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith by Thomas Keneally and the short story by David Malouf: "The Only Speaker of his Tongue".[citation needed]

Histories covering Indigenous themes include The Native Tribes of Central Australia by Spencer and Gillen, 1899; the diaries of Donald Thompson on the subject of the Yolngu people of Arnhem Land (c.1935–1943); Geoffrey Blainey (Triumph of the Nomads, 1975); Henry Reynolds (The Other Side of the Frontier, 1981); and Marcia Langton (First Australians, 2008). Differing interpretations of Aboriginal history are also the subject of contemporary debate in Australia, notably between the essayists Robert Manne and Keith Windschuttle.

AustLit's BlackWords project provides a comprehensive listing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Writers and Storytellers. The Living Archive of Aboriginal Languages contains stories written in traditional languages of the Northern Territory.

Film

Australian cinema has a long history and the ceremonies of Indigenous Australians were among the first subjects to be filmed in Australia – notably a film of Aboriginal dancers in Central Australia, shot by the anthropologist Baldwin Spencer in 1900.[153]

1955's Jedda was the first Australian feature film to be shot in colour, the first to star Aboriginal actors in lead roles, and the first to be entered at the Cannes Film Festival.[154] 1971's Walkabout was a British film set in Australia; it was a forerunner to many Australian films related to indigenous themes and introduced David Gulpilil to cinematic audiences. 1976's Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith, directed by Fred Schepisi, was an award-winning historical drama from a book by Thomas Keneally about the tragic story of an Aboriginal bushranger. The canon of films related to Indigenous Australians also increased over the period of the 1990s and early 21st Century, with Nick Parson's 1996 film Dead Heart featuring Ernie Dingo and Bryan Brown;[155]Rolf de Heer's Tracker, starring Gary Sweet and David Gulpilil;[156] and Phillip Noyce's Rabbit-Proof Fence[157] in 2002.

The 2006 film Ten Canoes was filmed entirely in an indigenous language, and the film won a special jury prize at the Cannes Film Festival.[158]

Traditional recreation and sport

1857 depiction of the Jarijari (Nyeri Nyeri) people near Merbein engaged in recreational activities, including a type of Aboriginal football.[159][160][161]

Aboriginal cricket team with Tom Wills (coach and captain), Melbourne Cricket Ground, December 1866

Though lost to history, many traditional forms of recreation were played and while these varied from tribe to tribe, there were often similarities. Ball games were quite popular and played by tribes across Australia, as were games based on use of weapons. There is extensive documented evidence of traditional football games being played. Perhaps the most documented is a game popularly played by tribes in western Victorian regions of the Wimmera, Mallee and Millewa by the Djab wurrung, Jardwadjali and Jarijari people. Known as Marn Grook, it was a type of kick and catch football game played with a ball made of possum hide, the existence of which was corroborated in accounts from European eyewitnesses and depicted in illustration.[162] According to some accounts, it was played as far away as the Yarra Valley by the Wurundjeri people,[163]Gippsland by the Gunai people, and the Riverina in south-western New South Wales. Since the 1980s it has been speculated that Marn Grook influenced Australian rules football, however there is no direct evidence in its favour.

A team of Aboriginal cricketers toured England in 1868, making it the first Australian sports team to travel overseas. Cricketer and Australian rules football pioneer Tom Wills coached the team in an Aboriginal language he learnt as a child, and Charles Lawrence accompanied them to England. Johnny Mullagh, the team's star player, was regarded as one of the era's finest batsmen.

Lionel Rose earned a world title in boxing. Evonne Goolagong became the world number-one ranked female tennis player with 14 Grand Slam titles. Arthur Beetson, Laurie Daley and Gorden Tallis captained Australia in Rugby League and the annual NSW Koori Knockout and Murri Rugby League Carnival. Mark Ella captained Australia in Rugby Union. Notable Aboriginal athletes include Cathy Freeman who earned gold medals in the Olympics, World Championships, and Commonwealth Games. In Australian football, an increasing number of Indigenous Australians are playing at the highest level, the Australian Football League.[citation needed]Graham Farmer is said to have revolutionised the game in the ruck and handball areas. Two Indigenous Team of the Century players, Gavin Wanganeen and Adam Goodes, have also been Brownlow Medal lists. Goodes was also the Australian of the Year for 2014. Two basketball players, Nathan Jawai and Patty Mills, have played in the sport's most prominent professional league, the National Basketball Association.

Aboriginal Australia has since been represented by various sporting teams, including the Indigenous All-Stars, Flying Boomerangs, the Indigenous Team of the Century (Australian rules football), Indigenous All Stars (rugby league) and the Murri Rugby League Team.

Technology

The scar on this tree is where Aboriginal people have removed the bark to make a canoe, for use on the Murray River. It was identified near Mildura, Victoria and is now in the Mildura Visitor Centre.

Technology used by indigenous Australian societies before European contact included weapons, tools, shelters, watercraft, and the message stick. Weapons included boomerangs, spears (sometimes thrown with a woomera) with stone or fishbone tips, clubs, and (less commonly) axes. The stone age tools available included knives with ground edges, grinding devices, and eating containers. Fibre nets, baskets, and bags were used for fishing, hunting, and carrying liquids. Trade networks spanned the continent, and transportation included canoes. Shelters varied regionally, and included wiltjas in the Atherton Tablelands, paperbark and stringybark sheets and raised platforms in Arnhem Land, whalebone huts in what is now South Australia, stone shelters in what is now western Victoria, and a multi-room pole and bark structure found in Corranderrk.[164] A bark tent or lean-to is known as a humpy, gunyah, or wurley.

Clothing included the possum-skin cloak in the southeast and riji (pearl shells) in the northeast.

Genetics

Indigenous Australian men have Haplogroup C-M347 in high frequencies with estimates going up to

60.2%[165] -68.7%.[166] In addition, the basal form K2* (K-M526) of the extremely ancient Haplogroup K2 – whose subclades Haplogroup R, haplogroup Q, haplogroup M and haplogroup S can be found in the majority of Europeans, Northern South Asians, Native americans and the Indigenous peoples of Oceania – has only been found in living humans today amongst Indigenous Australians. 27% of them may carry K2* and approximately 29% of Aboriginal Australian males belong to subclades of K2b1, a.k.a. M and S.[167]

Indigenous Australians possess deep rooted clades of both mtDNA Haplogroup M and Haplogroup N[168]

Population

Definition

Over time Australia has used various means to determine membership of ethnic groups such as lineage, blood quantum, birth and self-determination. From 1869 until well into the 1970s, Indigenous children under 12 years of age, with 25% or less Aboriginal blood were considered "white" and were often removed from their families by the Australian Federal and State government agencies and church missions, under acts of their respective parliaments in order that they would have "a reasonable chance of absorption into the white community to which they rightly belong".[169] Grey areas in determination of ethnicity led to people of mixed ancestry being caught in the middle of divisive policies which often led to absurd situations:[170]

In 1935, an Australian of part Indigenous descent left his home on a reserve to visit a nearby hotel where he was ejected for being Aboriginal. He returned home but was refused entry to the reserve because he was not Aboriginal. He attempted to remove his children from the reserve but was told he could not because they were Aboriginal. He then walked to the next town where he was arrested for being an Aboriginal vagrant and sent to the reserve there. During World War II he tried to enlist but was rejected because he was an Aborigine so he moved to another state where he enlisted as a non-Aborigine. After the end of the war he applied for a passport but was rejected as he was an Aborigine, he obtained an exemption under the Aborigines Protection Act but was now told he could no longer visit his relatives as he was not an Aborigine. He was later told he could not join the Returned Servicemens Club because he was an Aborigine.[170]

In 1983 the High Court of Australia[171] defined an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander as "a person of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander descent who identifies as an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander and is accepted as such by the community in which he or she lives".

The ruling was a three-part definition comprising descent, self-identification and community identification. The first part – descent – was genetic descent and unambiguous, but led to cases where a lack of records to prove ancestry excluded some. Self- and community identification were more problematic as they meant that an Indigenous person separated from her or his community due to a family dispute could no longer identify as Aboriginal.

As a result, there arose court cases throughout the 1990s where excluded people demanded that their Aboriginality be recognised. As a result, lower courts refined the High Court test when subsequently applying it. In 1995, Justice Drummond in the Federal Court held in Gibbs v Capewell "..either genuine self-identification as Aboriginal alone or Aboriginal communal recognition as such by itself may suffice, according to the circumstances." This contributed to an increase of 31% in the number of people identifying as Indigenous Australians in the 1996 census when compared to the 1991 census.[172] In 1998 Justice Merkel held in Shaw v Wolf that Aboriginal descent is "technical" rather than "real" – thereby eliminating a genetic requirement. This decision established that anyone can classify him or herself legally as an Aboriginal, provided he or she is accepted as such by his or her community.[173]

Inclusion in the National Census

Aboriginal boys and men in front of a bush shelter, Groote Eylandt, c. 1933

As there is no formal procedure for any community to record acceptance, the primary method of determining Indigenous population is from self-identification on census forms.

Until 1967, official Australian population statistics excluded "full-blood aboriginal natives" in accordance with section 127 of the Australian Constitution, even though many such people were actually counted. The size of the excluded population was generally separately estimated. "Half-caste aboriginal natives" were shown separately up to the 1966 census, but since 1971 there has been no provision on the forms to differentiate "full" from "part" Indigenous or to identify non-Indigenous persons who are accepted by Indigenous communities but have no genetic descent.[174]

In the 2011 Census, there was a 20% rise in people who identify as Aboriginal. One explanation for this is: "the definition being the way it is, it's quite elastic. You can find out that your great-great grandmother was Aboriginal and therefore under that definition you can identify. It's that person's right to identify so ... that's what explains the large increase."[175]

Demographics

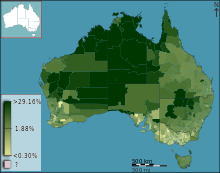

State distribution and identification growth rate

The Australian Bureau of Statistics 2005 census of Australian demographics showed that the Indigenous population had grown at twice the rate of the overall population since 1996 when the Indigenous population stood at 283,000. The Australian Bureau of Statistics estimated the total resident Indigenous population to be 458,520 in June 2001 (2.4% of Australia's total), 90% of whom identified as Aboriginal, 6% Torres Strait Islander and the remaining 4% being of dual Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander parentage. Much of the increase since 1996 can be attributed to greater numbers of people identifying themselves as Aboriginal or of Aboriginal descent. Changed definitions of Aboriginality and positive discrimination via material benefits have been cited as contributing to a movement to indigenous identification.[94]

In the 2016 Census, 590,056 respondents declared they were Aboriginal, 32,345 declared they were Torres Strait Islander, and a further 26,767 declared they were both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders.[176] The total Indigenous population was estimated to be 649,171, representing about 2.8% of the population.[176]

Based on census data, the preliminary estimate of Indigenous resident population of Australia was 649,171, broken down as follows:

New South Wales – 216,176

Queensland – 186,482

Western Australia – 75,978

Northern Territory – 58,248

Victoria – 47,788

South Australia – 34,184

Tasmania – 23,572

Australian Capital Territory – 6,508- and a small number in other Australian territories[176]

The state with the largest total Indigenous population is New South Wales. Indigenous Australians constitute 2.9% of the overall population of the state. The Northern Territory has the largest Indigenous population in percentage terms for a state or territory, with 25.5% of the population being Indigenous.

In all of the other states and territories, less than 5% of their total population identifies as Indigenous; Victoria has the lowest percentage at 0.8%.[176]

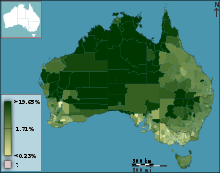

Urbanisation rate

In 2006 about 31% of the Indigenous population was living in "major cities" (as defined by the Australian Bureau of Statistics/Australian Standard Geographical Classification) and another 45% in "regional Australia", with the remaining 24% in remote areas. The populations in Victoria, South Australia, and New South Wales are more likely to be urbanised.[177]

Intermarriage rate

The proportion of Aboriginal adults married (de facto or de jure) to non-Aboriginal spouses increased to 74% according to the 2011 census,[178] up from 71% in 2006, 64% in 1996, 51% in 1991 and 46% in 1986. The census figures show there were more intermixed Aboriginal couples in capital cities: 87% in 2001 compared to 60% in rural and regional Australia.[179] It is reported that up to 88% of the offspring of mixed marriages subsequently self identify as Indigenous Australians.[172]

Groups and communities

Aboriginal farmers in Victoria, 1858

Throughout the history of the continent, there have been many different Aboriginal groups, each with its own individual language, culture, and belief structure.

At the time of British settlement, there were over 200 distinct languages.[180]

There are an indeterminate number of Indigenous communities, comprising several hundred groupings. Some communities, cultures or groups may be inclusive of others and alter or overlap; significant changes have occurred in the generations after colonisation.

The word "community" is often used to describe groups identifying by kinship, language or belonging to a particular place or "country". A community may draw on separate cultural values and individuals can conceivably belong to a number of communities within Australia; identification within them may be adopted or rejected.

An individual community may identify itself by many names, each of which can have alternate English spellings. The largest Aboriginal communities – the Pitjantjatjara, the Arrernte, the Luritja and the Warlpiri – are all from Central Australia.

Indigenous "communities" in remote Australia are typically small, isolated towns with basic facilities, on traditionally owned land. These communities have between 20 – 300 inhabitants and are often closed to outsiders for cultural reasons. The long term viability and resilience of Indigenous communities has been debated by scholars[181] and continues to be a political issue receiving fluctuating media attention.

Tasmania

Robert Hawker Dowling, Group of Natives of Tasmania, 1859

The Tasmanian Aboriginal population are thought to have first crossed into Tasmania approximately 40,000 years ago via a land bridge between the island and the rest of mainland Australia during the last glacial period.[182] Estimates of the population of the Aboriginal people of Tasmania, before European arrival, are in the range of 3,000 to 15,000 people although genetic studies have suggested significantly higher figures, which are supported by Indigenous oral traditions that indicate a reduction in population from diseases introduced by British and American sealers before settlement.[183][f] The original population was further reduced to around 300 between 1803 and 1833 due to disease,[184] warfare and other actions of British settlers.[185] Despite over 170 years of debate over who or what was responsible for this near-extinction, no consensus exists on its origins, process, or whether or not it was genocide. However, using the "UN definition, sufficient evidence exists to designate the Tasmanian catastrophe genocide."[183]

A woman named Trugernanner (often rendered as Truganini) who died in 1876, was, and still is, widely believed to be the very last of the full-blooded Aborigines. However, in 1889 Parliament recognised Fanny Cochrane Smith (d:1905) as the last surviving full-blooded Tasmanian Aborigine.[g][h] The 2006 census showed that there were nearly 17,000 Indigenous Australians in the State.

Contemporary issues

The Indigenous Australian population is a mostly urbanised demographic, but a substantial number (27% in 2002[186]) live in remote settlements often located on the site of former church missions. The health and economic difficulties facing both groups are substantial. Both the remote and urban populations have adverse ratings on a number of social indicators, including health, education, unemployment, poverty and crime.[187]

In 2004, Prime Minister John Howard initiated contracts with Aboriginal communities, where substantial financial benefits are available in return for commitments such as ensuring children attend school. These contracts are known as Shared Responsibility Agreements. This saw a political shift from "self determination" for Aboriginal communities to "mutual obligation",[188] which has been criticised as a "paternalistic and dictatorial arrangement".[189]

Identity

Who has the right to identify as indigenous has become an issue of controversy. The prominent Aboriginal activist Noel Pearson has stated: "The essence of indigeneity … is that people have a connection with their ancestors whose bones are in the soil. Whose dust is part of the sand. I had to come to the somewhat uncomfortable conclusion that even Andrew Bolt was becoming Indigenous because the bones of his ancestors are now becoming part of the territory."[190]

Stolen Generations

| Part of a series on |

| Indigenous rights |

|---|

Rights |

|

Governmental organizations |

|

NGOs and political groups |

|

Issues |

|

Legal representation |

|

Category |

The term Stolen Generations refers to those children of Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent who were forcibly removed[191] from their families by the Australian Federal and State government agencies and church missions for the purpose of eradicating Aboriginal culture, under acts of their respective parliaments.[i][192] The forcible removal of these children occurred in the period between approximately 1871[193] and 1969,[194][195] although, in some places, children were still being taken in the 1970s.[j]

To this day, this forced removal has had a huge impact on the psyche of Aboriginal Australians; it has seriously impacted not only the children removed and their parents, but their descendants as well. Not only were many of the children abused – psychologically, physically, or sexually – after being removed and while living in group homes or adoptive families, but were also deprived of their culture alongside their families.[196] This has resulted in the disruption of Aboriginal oral culture, as families were unable to communicate their knowledge to the Stolen Generations, and thus much has been lost.[196] There is also high incidences of anxiety, depression, PSTD and suicide amongst the Stolen Generations, with this resulting in unstable parenting and family situations.[196]

An inquiry into the Stolen Generations was launched in 1995 by the Keating government, and the final report delivered in 1997 – the Bringing Them Home report – estimated that around 10 to 33% of all Aboriginal children had been separated from their families for the duration of the policies.[196] The then-Howard government largely ignored the recommendations provided by the report, one of which was a formal apology to Aboriginal Australians for the Stolen Generations.[196] There was a formal apology issued on 13 February 2008 by Prime Minister Kevin Rudd on behalf of the federal government of Australia to the Aboriginal Australians over the Stolen Generations.[197]

Political representation

Under Section 41 of the Australian Constitution, Aboriginal Australians always had the legal right to vote in Australian Commonwealth elections if their State granted them that right. This meant that all Aboriginal peoples outside Queensland and Western Australia had a legal right to vote. The right of Indigenous ex-servicemen to vote was affirmed in 1949 and all Indigenous Australians gained the unqualified right to vote in Federal elections in 1962.[198] Unlike other Australians, however, voting was not made compulsory for Indigenous people.

It was not until the repeal of Section 127 of the Australian Constitution in 1967 that Indigenous Australians were counted in the population for the purposes of distribution of electoral seats. Six Indigenous Australians have been elected to the Australian Senate: Neville Bonner (Liberal, 1971–1983), Aden Ridgeway (Democrat, 1999–2005), Nova Peris (Labor, 2013–2016), Jacqui Lambie (2014–2017), Pat Dodson (Labor, 2016– incumbent), and former Northern Territory MLA Malarndirri McCarthy (Labor, 2016– incumbent). Following the 2010 Australian Federal Election, Ken Wyatt of the Liberal Party won the Western Australian seat of Hasluck, becoming the first Indigenous person elected to the Australian House of Representatives.[199][200] His nephew, Ben Wyatt was concurrently serving as Shadow Treasurer in the Western Australian Parliament and in 2011 considered a challenge for the Labor Party leadership in that state.[201] In March 2013, Adam Giles of the Country Liberal Party became Chief Minister of the Northern Territory – the first indigenous Australian to become head of government in a state or territory of Australia.[202]

A number of Indigenous people represent electorates at State and Territorial level and South Australia has had an Aboriginal Governor, Sir Douglas Nicholls. The first Indigenous Australian to serve as a minister in any government was Ernie Bridge, who entered the Western Australian Parliament in 1980. Carol Martin was the first Aboriginal woman elected to an Australian parliament (the Western Australian Legislative Assembly) in 2001, and the first woman minister was Marion Scrymgour, who was appointed to the Northern Territory ministry in 2002 (she became Deputy Chief Minister in 2008).[198] Representation in the Northern Territory has been relatively high, reflecting the high proportion of Aboriginal voters. The 2012 Territory election saw large swings to the conservative Country Liberal Party achieved in remote Territory electorates and a total of five Aboriginal CLP candidates won election to the Assembly (along with one Labor candidate) in a chamber of 25 members. Among those elected for the CLP were high-profile activists Bess Price and Alison Anderson.[203]

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC), a representative body of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, was set up in 1990 under the Hawke government. In 2004, the Howard government disbanded ATSIC and replaced it with an appointed network of thirty Indigenous Coordination Centres that administer Shared Responsibility Agreements and Regional Partnership Agreements with Aboriginal communities at a local level.[204]

In October 2007, just before the calling of a federal election, the then Prime Minister, John Howard, revisited the idea of bringing a referendum to seek recognition of Indigenous Australians in the Constitution (his government first sought to include recognition of Aboriginal peoples in the Preamble to the Constitution in a 1999 referendum). His 2007 announcement was seen by some as a surprising adoption of the importance of the symbolic aspects of the reconciliation process, and reaction was mixed. The ALP initially supported the idea, however Kevin Rudd withdrew this support just before the election – earning stern rebuke from activist Noel Pearson.[205] Critical sections of the Australian public and media[206] meanwhile suggested that Howard's raising of the issue was a "cynical" attempt in the lead-up to an election to "whitewash" his handling of this issue during his term in office. David Ross of the Central Land Council was sceptical, saying "it's a new skin for an old snake",[207]

while former Chairman of the Reconciliation Council Patrick Dodson gave qualified support, saying: "I think it's a positive contribution to the process of national reconciliation...It's obviously got to be well discussed and considered and weighed, and it's got to be about meaningful and proper negotiations that can lead to the achievement of constitutional reconciliation."[208]

The Gillard Government, with bi-partisan support, convened an expert panel to consider changes to the Australian Constitution that would see recognition for Indigenous Australians. The Government promised to hold a referendum on the constitutional recognition of indigenous Australians on or before the federal election due for 2013.[209] The plan was abandoned in September 2012, with Minister Jenny Macklin citing insufficient community awareness for the decision.

Australian politicians of Indigenous ancestry

Only 32 people recognised to be of Indigenous Australian ancestry have been members of the ten Australian legislatures.[citation needed][when?]

The Northern Territory has an exceptionally high Indigenous proportion – about one third of its population – and a greater rate of Indigenous politicians within the Northern Territory parliament. Adam Giles, who became Chief Minister of the Northern Territory in 2013, is the first Indigenous head of government in Australia.

Major political parties in Australia have tried to increase the number of Indigenous representation within their parties. A suggestion for increasing the number of Indigenous representation has been the introduction of seat quotas like the Maori electorates in New Zealand.

Age characteristics

The Indigenous population of Australia is much younger than the non-Indigenous population, with an estimated median age of 21 years (37 years for non-Indigenous), due to higher rates of birth and death.[210] For this reason, age standardisation is often used when comparing Indigenous and non-Indigenous statistics.[186]

Life expectancy

The life expectancy of Indigenous Australians is difficult to quantify accurately. Indigenous deaths are poorly identified, and the official figures for the size of the population at risk include large adjustment factors. Two estimates of Indigenous life expectancy in 2008 differed by as much as five years.[211]

In some regions the median age at death was identified in 1973 to be as low as 47 years and the life expectancy gap between Aboriginal people and the rest of the Australian population as a whole, to be 25 years.

From 1996 to 2001, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) used indirect methods for its calculations, because census results were deemed to be unreliable,[citation needed] and figures published in 2005 (59.4 years for males and 64.8 years for females) indicated a widely quoted gap of 17 years between indigenous and non-indigenous life expectancy, though the ABS does not now consider the 2005 figures to be reliable.

Using a new method based on tracing the deaths of people identified as Indigenous at the 2006 census, in 2009 the ABS estimated life expectancy at 67.2 years for Indigenous men (11.5 years less than for non-Indigenous) and 72.9 years for Indigenous women (9.7 years less than for non-Indigenous). Estimated life expectancy of Indigenous men ranges from 61.5 years for those living in the Northern Territory to a high of 69.9 years for those living in New South Wales, and for Indigenous women, 69.2 years for those living in the Northern Territory to a high of 75.0 years for those living in New South Wales.[212][213][214][215]

Education

There is a significant gap between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people in terms of education. This presents significant issues for employment. Overall, Aboriginal students:

- Have a lower attendance rate than non-Aboriginal students nationally, with these rates at 83.5% and 93% respectively.[216]

- Are marked lower in NAPLAN testing than non-Aboriginal peers.[216]

- Have a lower Year 12 attainment than non-Aboriginal peers.[216]

- Are underrepresented in higher education and have lower completion rates (40.5% compared to 66.4%).[216]

Due to this, the Close the Gap campaign has focused on improving education for Aboriginal persons, with some success. Attainment of Year 12 or equivalent qualification for ages 20-24 has increased from 47.4% in 2006 to 65.3% in 2016, thus narrowing the gap by 12.6 percentage points.[216] Furthermore, this completion of Year 12 qualifications has resulted in a greater number of Aboriginal persons undertaking higher education or vocational education courses. According to the Close the Gap report, "The number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students in higher education award courses has more than doubled over the past decade (from 8,803 in 2006 to 17,728 in 2016). In comparison, domestic award student enrolments increased by 46.2 per cent over the same period."[216] The attendance rate of Aboriginal students in primary and high schools has also remained steady.

However, while there has been some improvement, most of the Close the Gap targets for education are not on track, barring Year 12 attainment goals. In general, the gaps have improved – as with an improvement of NAPLAN results – or not devolved – as with the attendance rate remaining stable for several years – but unfortunately not to the standard required.[216] Remoteness does appear to be a factor, as students in remote areas do not perform or attend as well as students in urban areas.[216]

In response to this problem, the Commonwealth Government formulated a National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Education Policy. A number of government initiatives have resulted, some of which are listed at the Commonwealth Government's website.[217]

The Aboriginal Centre for the Performing Arts was established as a training centre by the State and Federal Governments in 1997.

Employment

Compared to national average, Aboriginal persons experience high unemployment and poverty rates. As of the 2018 Close the Gap report,[218] the Aboriginal employment rate had decreased from 48% in 2006 to 46.6% in 2016, while the non-Aboriginal employment rate remained steady at around 72%, making for a 25.4% gap between the two populations. However, while still remaining significantly lower than non-Aboriginal counterparts, the employment rate for Aboriginal women has increased from 39% in 2006 to 44.8% in 2016. These low employment rates suggest significant barriers to Aboriginal persons gaining employment, which may include job location, employer discrimination, and lack of education, amongst others.[219]